CARRBORO — Kaan Ozmeral was about 17 miles from his office Thursday morning as he tested students in one of his math classes.

He wasn’t in the same room as them, or in the same county for many. Instead, he was parked outside Weaver Street Market in Carrboro, sitting in his car on his laptop, with a test answer key scribbled on a piece of paper beside him.

Ozmeral teaches multiple math classes at Central Carolina Community College’s Pittsboro campuses. On a normal workday, he’d have access to both his students and the campus’ internet connection. But with in-person classes canceled, campus closed and all work being done online, he had to find a different way to connect.

Why?

His home in northeast Chatham has no internet because service providers won’t come there.

“It’s a new neighborhood with nice houses,” Ozmeral said. “It’s not in the middle of nowhere. It was surprising. I had my house built and it finished a year ago. When I moved in, I was like, ‘Oh, I don’t have internet.’”

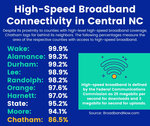

According to BroadbandNow.com, which measures internet connections and speeds across the country, 86.5 percent of Chatham residents have access to internet download speeds of 25 megabits per second and 82.7 percent of the county has access to some kind of coverage. That may sound like a lot, but at least 90 percent of residents in each of Chatham’s neighboring counties — Wake, Moore, Lee, Orange, Alamance and Randolph — have that kind of high-speed service available.

Chatham’s high-speed broadband service, or relative lack thereof, has been a talking point among local elected and economic officials for years. But the spread of COVID-19, moving school classes online and stay-at-home executive orders have made that deficiency much more visible.

Education gaps

On February 28, Chatham County leaders participated in a breakfast with the county’s state legislative members — Rep. Robert Reives II (D-Chatham) and Sen. Valerie Foushee (D-Orange). After discussing the need for a school construction bond, talk turned to needing more broadband internet access in rural areas.

“We are lacking that in many areas,” County Manager Dan LaMontagne said. “It’s extremely valuable to our students. Their homework is increasingly online. This is really a needed utility throughout the state.”

Thirteen days later, Gov. Roy Cooper signed an executive order closing all of North Carolina’s public schools for two weeks, a period later extended to May 15. This required schools to continue their education online — moving homework from “increasingly online” to completely online in a matter of days. Speaking to the News + Record last week, LaMontagne rebuffed suggestions of prophecy, but held firm to his position.

“I’d say it couldn’t be more true right now,” he said. “This is just a prime example of that. Who knew that this would be the way our students are trying to learn and coming into the close of the semester?”

Chatham County Schools and Central Carolina Community College, which has three campuses in Chatham County, have moved all classes online, and each institution is finding that some students are having a hard time completing assignments and staying in touch with teachers.

CCCC Chatham Provost Mark Hall said the college moved modems in its buildings to windows in order to provide internet connection to students and faculty who park in parking lots. Others, he said, are using the Wi-Fi at Lowe’s Hardware in Pittsboro.

“(Students) don’t have internet or all they have is DSL,” Hall said. DSL, which utilizes existing telephone lines, provides a lower bandwidth and less powerful connection.

“Some providers have a better infrastructure than others,” Hall contined. “The way we live and work these days and learn, it’s essential to have broadband internet to do that in an efficient way. It’s going to get hot soon — it’s not fun to sit in parking lots and use Wi-Fi.”

Tripp Crayton, the principal at Jordan-Matthews High School in Siler City, said 18 percent of his students — around 90 people — don’t have internet access at home and thus have to use paper packets to learn. That prohibits timely feedback, if feedback is given at all. The district has been handing out internet hotspots and laptops, but those hotspots use cell service, which is not always reliable.

“Just because a kid has a hotspot doesn’t mean they get equal access as those who have full internet,” Crayton said. “Hotspots can be slow. It counts on a student having cell service on their phone.”

Education is an area in which equity and each person getting the same experience is not only paramount but enshrined in state law — N.C. General Statute 115C-1 says that public schools should provide “equal opportunities...for all students” to align with Article IX of the state constitution. Amanda Hartness, the district’s assistant superintendent of academic service and instructional support, says internet “inequities” has been CCS’ “biggest challenge” during COVID-19.

“We do have students and staff who aren’t getting the same experience,” she said.

Wanting to fill the gap

A little more than two years ago, the N.C. League of Municipalities released a report entitled “Leaping the Digital Divide” which chronicled the need for public investment in broadband connection, particularly in rural areas.

“Few people today question that broadband has become essential infrastructure, fundamental to commerce, education, health care and entertainment,” the report stated. “Nonetheless, more than two decades into the digital revolution, many areas of North Carolina lack access to adequate broadband service, and even densely-populated areas can lack the kinds of internet speeds needed for business to thrive.”

Chatham County is one of those areas. According to BroadbandNow.com, only 82.7 percent of Chatham has access to high-speed broadband coverage, compared to 95.2 percent of the state. The Town of Siler City has 79.4 percent total coverage and 10 providers, and Pittsboro has 85 percent and 12, respectively.

And what Chatham already has does not rank highly. CenturyLink is one of Chatham’s major providers and, according to BroadbandNow, its average speed statewide is 30.2 megabits per second. That’s less than a third of the speed of AT&T Internet (99.5 MBPS) and less than half of what Charter Spectrum provides (71.6 MBPS).

It’s not that CenturyLink is unable to provide quick service in Chatham. In March 2018, the company announced it would be offering speeds of “up to 1 gigabit per second” to residents in the soon-to-be-built Chatham Park and up to 10 gigabits per second for businesses in the development.

“We are excited to expand our fiber network in Chatham County, the sixth-fastest growing county in North Carolina, so we can enhance Chatham Park with a powerful network that delivers exceptional broadband service,” Erik Genrich, senior director for the southeast region of CenturyLink, said in a press release. “We look forward to working closely with Chatham Park and other forward-thinking developers who understand the value of reliable and fast connectivity.”

Since internet service providers are private businesses, they are by no means required to provide connection to all residents, but officials have criticized them for providing inaccurate information to the Federal Communications Commission and local governments. This article utilizes FCC-collected data, which uses census tracts instead of individual houses and plots of land to determine service rates, making it possible that service capability is actually smaller than reported. A note from the North Carolina Broadband Infrastructure Office, which also tracks service capability, states that broadband being within an area does not necessarily mean the entire area is covered, but that ISPs “may not necessarily offer that service everywhere in the block.”

During the Feb. 28 legislative breakfast, county leaders asked for state legislators to push for more accurate reporting — including “the telecoms report(ing) all addresses served and the speed of service,” according to the meeting’s agenda packet — to give a better picture of real service.

Internet as a utility

What’s required, according to LaMontagne, is re-framing the discussion around internet not as a luxury, but a needed utility like water and electricity, and COVID-19 is displaying that.

“It’s the old days of telephone,” he said. “Back when telephones first came out, that’s how you got emergency services. You needed a telephone in every home. Internet is that way now. Everybody knows that. They need internet service. It is in my mind, absolutely utility, but it’s not being treated as one yet.”

The League of Municipalities report echoed LaMontagne’s sentiments.

“High-speed broadband is now fundamental to commerce, education and health care in North Carolina,” he said. “It is essential 21st-century infrastructure, and as with roads and bridges, communities that are not adequately connected to the larger network cannot and will not succeed economically.”

The economic benefits that come with better internet access and speeds are one of the key selling points of a common plea for rural areas: getting the local government involved in providing broadband for residents.

Blair Levin is a senior fellow with the Brookings Institution, a nonprofit public policy organization in Washington, D.C. He wrote the introduction to the “Leaping the Digital Divide” report, arguing that public investment was a must. More broadband in areas, he said, was connected to higher per capita gross domestic product, higher revenues for home businesses connected to high-speed connections and improved property values.

“If a community wants to thrive in the economy and society of the decades to come, it needs a network capable of carrying that kind of traffic,” Levin wrote. “There is no silver bullet that works for every community. But there is a bullet that can kill every community — doing nothing.”

Chatham County wants to do something. The county’s website — which does not normally serve as an advocacy tool — states that the county government “shares the concerns of many residents who have limited or no access to broadband service.”

“This situation is not acceptable and we continue to work on this issue,” the website states. “The bottom line is that there are few real incentives for cable and telephone companies to expand coverage in rural areas. The State of North Carolina also has substantially restricted what counties can do in partnering with broadband providers.”

Hurdles to jump

Only one government entity is in the broadband internet business — the City of Wilson, a little more than 80 miles from downtown Pittsboro. In 2007, Wilson began building its own fiber system after the area’s cable provider declined offers to buy its services in the area and partner with the city to update its network.

According Greenlight Community Broadband, the city’s publicly-owned service, that private provider then sought support for state legislation to prohibit Wilson’s efforts. Such legislation eventually passed, but Wilson was grandfathered in with some limitations — they couldn’t go past the Wilson County line, despite the county providing electrical services to six counties, and if a private provider began offering services in a market, the City would have to shut down its network in that area. That happened with the nearby town of Pinetops, which went from near-top-level speed of 1 gigabit per second for downloads to 50 megabits per second when a private provider came in. One gigabit translates to 1,000 megabits.

The 2011 legislation has proven to be a roadblock to further municipal broadband services or even allowing counties and cities to participate with private companies in offering services to residents. In a 2019 report entitled “Municipal Broadband Is Roadblocked or Outlawed in 25 States,” BroadbandNow’s Kendra Chamberlain wrote that North Carolina’s laws “make it exceedingly difficult for public entities to deploy broadband services to residents.”

Chatham officials discussed this legislation and their desire to see it changed at the February 28 breakfast.

“We all need to be coalescing around the issue,” Chatham County Commission Chairman Karen Howard said at the meeting, referring to county-level government officials in the central North Carolina region. “It’s completely nonpartisan, and the people that are hurting the most are the people who don’t have a voice to access the powers that do. Comprehensive coverage everywhere in the state (is) an issue of equity.”

Reives said at that meeting that there is appetite to change in the state legislature, but Raleigh’s power players are not on board.

“This is a problem that can be solved immediately,” Reives said. “You’ve got enough votes in the Senate and enough votes in the House to basically repeal the Wilson bill. But you can’t get leadership. This is one of those issues that this isn’t partisan. It’s kind of ridiculous that you’re allowing legislators to sit there and think, ‘We don’t ought to do this right now,’ because everybody’s hurting.”

That leadership includes House Speaker Tim Moore (R-King’s Mountain) and Senate Leader Phil Berger (R-Rockingham). According to the N.C. State Board of Elections, Berger and Moore’s campaigns each received $4,400 from the AT&T PAC out of Raleigh in the first quarter of 2020. In the second half of 2019, Berger received $3,000 from the CenturyLink Employees PAC and $5,400 from the Charter Communications NC PAC, while Moore was the beneficiary of a $2,500 donation from the CenturyLink Employees PAC and $5,400 from the Charter Communications NC PAC.

On the other hand, Reives, the Deputy Democratic Leader in the N.C. House received $250 from the CenturyLink Employees PAC in the second half of 2019.

What Chatham can do

Right now, what Chatham County can actually do turns out to be very little. There’s a lot it wants to do, LaMontagne said. Not necessarily starting its own broadband service, but providing the infrastructure to encourage private ISPs to extend access to more rural areas.

“We’d like to be able to provide our vertical assets, so towers, water tanks, things like that to the providers,” LaMontagne said. “We’d like to be able to install fiber, fiber-optic cable, and let that be leased out to different internet service providers. We would help with the capital expense of getting it out to these rural areas. There’s any number of options for that we could look at for this. That’s just the simplest to me, is just let us help get the providers to provide those services out into those unincorporated, these rural areas that are unincorporated.”

He said that he hopes COVID-19 and the number of people working from home with poor or no internet, utilizing hotspots or driving to parking lots, will “push us over the edge” in this conversation.

Chatham County Schools has already taken a step toward improving its service on its own. The school board agreed a contract last March with Charlotte-based Conterra Ultimate Broadband to lay 88 miles of fiber optic broadband throughout the county, connecting to all of the district’s 19 current locations and two future spots.

Keith Medlin, Chatham County Schools’ director of technology and communications, said at the time it would provide better service for the schools and that the county government may be able to take advantage too.

“This gives us a long-term contract and speeds that won’t have prices that change,” Medlin said. “This is a core part of the first step we can take to help attract a vendor to lay this much fiber within Chatham County. It will give the county an opportunity to do a separate negotiation.”

At the time, LaMontagne said the county is anticipating a few facilities being connected to the fiber and saw the whole line as infrastructure laid for a service provider in the future.

Until then, Ozmeral, who lives in northeast Chatham in a “new-ish” neighborhood, will need to drive somewhere to do his job while COVID-19 is in play.

“I sit in a parking lot all day with my laptop and my phone and my books,” he said. “I’m making it work. It’s been nice weather so it’s been nice sitting.”

Reporter Zachary Horner can be reached at zhorner@chathamnr.com or on Twitter at @ZachHornerCNR.