“I thought I was dead,” said U.S. Army veteran Sgt. Brent Patterson, recalling the confusion in the unsettled moments following an explosion in Afghanistan that left him and his buddies momentarily stunned amid smoke, dust and rubble.

“The building we were in fell on top of us,” the former infantryman recalled. “Everything was quiet and black. When you get hit that hard,it takes a minute for everything to come back.”

Surrounded by injured squad members — one sustained a broken neck in the explosive IED assault — Patterson, though injured himself, began scrambling to help, providing first aid to his fellow wounded.

While Patterson said the July 2011 incident is “burned in his brain,” it wasn’t the first, or last time, the young soldier would come under fire during his final deployment in Afghanistan’s mountainous Charkh district.

While there, Patterson survived three separate attacks by Taliban forces — all within the same small village, and, though separated by months, all within a small radius — sustaining shrapnel injuries in all three of the violent encounters.

Patterson’s heroism while wounded and facing intense enemy fire would later be recognized with the awarding of three Purple Hearts.

But his wartime experience also influenced his life in ways he couldn’t have foreseen at the time, particularly in the work he has undertaken more recently in a college laboratory in Maryland.

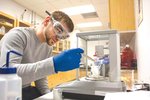

As a student majoring in materials engineering at Frostburg University, Patterson has been working on developing new, organic bullet resistant materials.

It’s something Patterson, a Pennsylvania native who later moved with his parents to Chatham County, likely would not have envisioned for himself while a at student at Northwood High School, where he graduated in 2006.

“It was good,” Patterson said of his high school years, but admits in the next breath that, during his teens, he wasn’t the most academically-motivated student, failing Algebra II and demonstrating little interest in science classes.

“I didn’t take high school very seriously,” he said. “I literally met the basic, minimum standards of Northwood. But I did graduate.”

His relatively uninspired high school performance may have been because he already had plans for life after graduation: to work alongside his father in mechanics.

And Patterson did just that after graduating, working for his father’s business, performing mechanical work on tractor trailers. He did that for a while before his father encouraged him to join the military. “He wanted me to be completely happy,” Patterson said.

It was a path he’d already considered. A middle-schooler when the 9/11 terror attacks occurred in 2001, Patterson wanted to help.

“I wanted to go fight,” he said. “And I got my wish.”

He researched the various branches of the military, choosing the Army and, following four months of Army training, spent the next five years in military service, 27 months of that time overseas.

He found himself at loose ends once more when his military service ended.

“Basically, I didn’t know what to do,” he said. “I wasn’t the person I wanted to be.”

The young veteran ultimately made a decision to use his military benefits to advance his education. He enrolled at Frostburg University, but still had some more soul-searching to do to find the right major. Dreaming of opening his own gun shop, he first majored in business management. But that wasn’t the right fit. He briefly considered architecture as a prospective field, but that didn’t stick either.

He eventually honed in on engineering, the “only career choice I could see myself being happy with.”

“I completely committed to it,” he said, “always doing homework and studying. I grew up.”

His military career — particularly the harrowing combat he’d experienced in Afghanistan — would prove to be instrumental in his schooling, guiding him towards, and informing, the work he’s currently doing at Frostburg to create a better, organic bulletproof material.

Under fire overseas, Patterson had experienced the shortcomings of available bulletproof materials, including Kevlar, the strong synthetic fiber developed at Dupont in 1965 and used commercially in various applications since the early 70s, particularly body armor.

“Kevlar is a bunch of super-strong fiber woven together,” Patterson said. But when wet, he noted, bullets are able to penetrate “through the cracks.”

For his college capstone project, conducting independent research to address a problem of his choosing, the Army veteran said he “wanted to do something bulletproof related.”

The result is his student research project, “Organic Bullet Resistance: Pushing the Capabilities of Nanocellulose,” which he and his team members undertook to work toward creating a sustainable, next-generation bullet-resistant material using nanocellulose, an ultra-fine, nano-structured form of cellulose first identified in the early 1980s and only commercially available since 2010.

Patterson knew, in theory, that nanocellulose could be used to develop material stronger than steel or Kevlar, but no one had yet demonstrated that.

Last fall, he presented his project at the Materials Science & Technology Conference in Ohio, where his presentation drew much attention.

But Patterson, who will graduate in May, said work still remains to meet his goal.

“We’re still a ways out,” he said. “The bullets are still penetrating.”

But he and his research team, comprised of three other students, have made advances. And it’s work Patterson said he hopes to continue to pursue after college. He envisions many useful applications for a successful nanocellulose product, perhaps even bulletproof shields that could be used in students’ backpacks for protection in the event of school shootings.

Patterson said his experiences as a soldier were rough, and he’s witnessed the devastating effects of such trauma on other soldiers. Some commit suicide, or engage in risky behavior as a coping mechanism.

“A lot of people struggle with it,” Patterson said. “For whatever reason, “I’ve been able to overcome it and learn from it. I would do it all over again. I really appreciate all my terrible experiences because it’s made me a better person.”