Larry Miller was as much a playboy as he was a basketball player at the University of North Carolina, an uber-talented forward who brought Dean Smith’s early Tar Heel teams to national prominence while also maintaining a work-hard-play-hard lifestyle he admitted was “a little bit at odds” with his coach.

As a pro, he kept the same shtick — once dubbed the Joe Namath of the America Basketball Association, Miller set the league’s single-game scoring record (67 points) while dabbling in acting classes at Universal Studios, partying in the Hollywood hills and winning an episode of ABC’s “The Dating Game.”

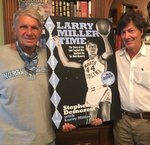

Miller, now 74, has since kept a low profile. But in a new book by author Stephen Demorest, released Monday, Miller rehashed those memories and more from a life full on them.

“It’s been a fun ride,” he said.

Miller and Demorest promoted their book — “Larry Miller Time: The Story of the Lost Legend Who Sparked the Tar Heel Dynasty” — last Thursday in a Zoom discussion hosted by McIntyre’s, an indy bookstore in Chatham County’s Fearrington Village. Around 30 guests (most of them Tar Heel fans) attended the hour-long session, primarily an open conversation between author and subject.

“I was a little nervous about it at first,” Miller said, “but I’m really happy with the outcome.”

And his UNC stardom isn’t the book’s only local tie.

Nancy Curlee Demorest, Stephen’s wife, grew up in Statesville as a rabid fan of late 1960s UNC basketball — and specifically a “movie-star handsome” forward who wore No. 44. When she and her friends played with Barbies, she wrote in the book’s foreword, they always “wound up stealing my little brother’s G.I. Joe to be Barbie’s boyfriend, who was now Larry Miller.” (Sorry, Ken.)

Decades later, the Demorests were driving up to Rhode Island for a vacation when Nancy realized they were passing through Catasauqua, Pennsylvania, the Lehigh Valley suburb where Miller starred in high school and now lived as a retiree.

“As a former professional writer and a constitutionally curious person, I couldn’t get this close to Catasauqua without checking him out,” Nancy, a lifelong UNC basketball fan, wrote.

On the Demorests’ two-week vacation, Nancy researched Miller’s whereabouts in the area. And on their return trip to North Carolina, she routed them to what she hoped was Miller’s door in Catasauqua, with Stephen waiting in the car, half-expecting a trespassing charge.

She knocked three times before walking out back and finding her childhood hero hard at work in his garden, where they had a “remarkably warm and relaxed conversation.”

Miller followed up with the Demorests a few days later, mailing them a friendly note, a headshot and an aging piece of fan mail he received in 1968. The sender: a young Nancy Curlee of Statesville.

Stephen, a former TV soap opera writer and music journalist, agreed with Miller early on to work as a conduit. It was his story. Demorest was just there to tell it.

“I wasn’t looking to do exposés from 1965,” the author said Thursday.

“As you started doing some drafts and showing me what you were going to include, and we agreed what not include — which was probably more important — I was more comfortable with it,” Miller said, laughing.

Across 338 pages, Demorest traced Miller’s path from Pennsylvania to North Carolina to California and beyond. He wrote in third person and relied heavily on archival news coverage to piece together game-related scenes and describe Miller’s play style, since “there was no ESPN then,” he joked.

“And you really did a good job,” Miller said.

At North Carolina, Miller was a 6-foot-4 forward with a smooth lefty jumper, a 21.8 points-per-game scorer and a knack for out-rebounding guys half a foot taller than him.

Miller remains the only Tar Heel with two ACC Player of the Year awards; he won in 1967 as a junior and 1968 as a senior. In both seasons, he was also a first-team All-American and the ACC Tournament MVP, as UNC won consecutive conference titles and appeared in the 1967 Final Four and 1968 championship game. All of those were firsts for Dean Smith, a young coach who’d been hung in effigy two years earlier.

“Larry was the winner who made Coach Smith a winner,” teammate Charlie Scott said in the book. “Everything starts with him.”

Demorest also chronicled Miller’s seven-year career in the ABA, a startup rival to the NBA in the 1970s full of big-money contracts, colorful uniforms and “chaotic management,” he wrote.

While in the league, Miller scored 67 points in a game for the Carolina Cougars in 1972; played star NFL running back Jim Brown one-on-one in two-drinks-deep basketball at a Hollywood party; and even had Wilt Chamberlain as a head coach when he played for the San Diego Conquistadors. (“He was just a figurehead,” Miller said. “He didn’t even show up for practices.”)

After leaving basketball in 1975, Miller worked in construction in Virginia Beach and Raleigh before returning to his hometown of Catasauqua, where, of course, he later met the Demorests.

Bobby Lewis, another former teammate, surprised Miller on last Thursday’s Zoom call. Lewis said he “enjoyed every minute” of the book, barely putting it down as he relived great memories from the late ‘60s. And, he said, Miller seemed “at peace” with his life and legacy in the book — something else he loved.

“I’m getting more mail than I’ve ever gotten!” said Lewis, a UNC star in his own right. “And all the mail says is: ‘Have you read the Larry Miller book?’”

Reporter Chapel Fowler can be reached at cfowler@chathamnr.com or on Twitter at @chapelfowler.