RAMSEUR — It started on the way to lunch one day in 6th grade. She called it the worst panic attack she’s ever had, and it was her first.

“I will never forget it,” says Abigail Paige Holmes, 14, now a 9th-grader at Chatham Charter School.

Without warning, Abigail started breathing heavily. Her eyes watered, her heart pounded. She started crying, hands shaking. Fellow students crowded around her in the lunchroom, asking if she wanted them to get a teacher or adult. No, she insisted, she didn’t want to make a scene; she wanted to keep it “on the down low,” in teen speak.

It took 20 minutes for her to calm down, she says now. But that 20 minutes wouldn’t be the only time spent in her short life trying to relax and overcome extreme anxiety.

In 7th grade, the depression came. Abigail started self-harming, cutting herself on her leg, hiding in her room so no one else would see. She knew people would notice — she spotted a teacher at gymnastics eyeing the scars — but she didn’t open up.

“You feel a lot of pain inside, and you don’t know how to take it out,” she says about self-harm. “It’s a release that makes people feel better. That’s just how they release it because they don’t know any other way to fix the problem.”

A teacher would call on Abigail in class, and she would freeze. She recalled one time when the correct answer was on the page right in front of her, and she said something else. The rest of the day she was angry with herself for how she messed up, worried that friends and classmates would be laughing at her or making jokes or judgements behind her back. She would ask friends if they had, but they didn’t remember her getting the answer wrong.

She didn’t eat much and, in her words, looked “like a skeleton.”

The depression and anxiety reached a boiling point one night. Abigail was alone in her home — her mother Jennifer, step-father David and sister Samantha were all gone. It was bad.

“I was like, ‘I think my plan is to down as many pills as I possibly can because I just want it all gone,” she said. “I just want to leave.’”

After 10 minutes of considering trying to end her own life, she decided she couldn’t do that to her family.

“That was when I was like, ‘I need to do something right now,’” Abigail said.

A common disease

Abigail is not alone in her experiences.

The mental health of America’s teenagers, and of Chatham County’s in particular, has risen to such prominence that the county’s government, public school system and other institutions have been trying to find more solutions to help the rising number of teens who struggle.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, a nonprofit focused on mental health education, 20 percent of American youth ages 13-18 currently live with a mental health condition. Fifty percent of all cases begin by age 14.

North Carolina’s numbers line up almost exactly. The N.C. School Mental Health Initiative, a 2016 study, showed that 19 percent of North Carolina students aged 8-15 years old have a mental health disorder, and the state Department of Health and Human Services said in 2016 that there were nearly 400,000 instances of mental health counseling sessions in the state’s public schools during the prior school year.

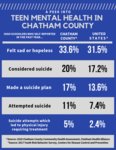

Thanks to the Chatham Health Alliance’s Community Health Assessment from earlier this year, officials were able to see that the problem has not skirted around the county. According to the study, 33.6 percent of Chatham high school students have “felt sad or hopeless” in the last year, 20 percent “seriously considered attempting suicide,” 17 percent “made a plan about how they would attempt suicide,” 11 percent actually attempted suicide and 5 percent had an attempt “that resulted in an injury, poisoning, or overdose that had to be treated by a doctor or nurse.”

Chatham is higher than the national average in all those categories, according to the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the number of high school students feeling sad or hopeless, seriously considering suicide and attempting suicide have all risen since 2014, according to the CHA.

Chatham County Health Director Layton Long can’t say why Chatham is higher, or why those numbers are the way they are, but they leave him with a question: “What are the issues that are causing kids to feel this way?”

On the frontlines

Share the same numbers with Jennifer Brannon, the student support specialist at Chatham Charter School, and her initial reaction is: “Oh my.”

But ultimately, it’s not surprising.

“I can think of some reasons for these numbers, just in the change in our world in general and how our teenagers are coping and what stressors they have that maybe we didn’t have as much of four years ago,” Brannon says.

The rise of active shooter drills in schools is just an example, she says, of teens feeling more unsafe in the world as they’ve seen some of their peers across the country slain in school shootings. Additionally, she’s seen more students under pressure in academics or athletics to “be the best” and more external pressures from social media networks.

“Teenagers are dealing with an inability to manage conflict because they haven’t had that face-to-face contact that you had in the ‘good old days,’” adds Samantha Mahon, a licensed clinical social worker who owns Peak Professional Group in Apex and Pittsboro. “You didn’t have all that technology back then.”

Mahon — who calls working with trauma, teens and tweens and women her particular “passions” in the field of counseling — says that teenage girls are facing additional stress from “devaluing of their bodies.”

“There’s a lot around sexuality,” she says. “Gender identity (and) sexual orientation is definitely coming to light more than it maybe has in previous years.”

Something nearly everyone who spoke to the News + Record for this story mentioned is a stigma around mental health issues, for both the parents and their children.

“I think that they face some struggles in obtaining mental health because a lot of them are not really aware that it’s OK to seek counseling,” Mahon says. “There’s still a lot of stigma in that particular area of life. Sometimes they want to be in therapy but then the parents don’t.”

For Chatham County in particular, access to mental health services was at one point limited, and statistics suggest that it might still be. According to the CHA, there are just 1.34 psychologists per 10,000 residents in Chatham County, compared to the North Carolina average of 10, and just 39.5 percent of residents know where to access mental health services.

Debra Henzey, Chatham County government’s director of community relations, also serves as the chair for the Mental Health Subcommittee of the Chatham Health Alliance. She and Long said that while there are resources in surrounding areas and access to tele-psychology (counseling sessions by phone or video conference) is growing, the relatively low number of people that don’t know where to find help is something they’re working on.

“That is a consistent problem in my years, that people don’t know,” Long said.

Henzey added, “It shows we still have a lot more work to do.”

Resources there

The county struggled to find a consistent and effective mental health safety net provider for years, Long said, until Daymark Recovery Services, a mental health and substance abuse services organization, established an office last year in Siler City to serve as the county’s partner. Henzey and Long praised the work Daymark has done, citing in particular the provider’s ability to take Medicaid payments and current patient satisfaction with the services. However, according to the CHA, only 6 percent of county residents said they were aware of what’s offered at Daymark.

So the biggest piece for the county is education. The health department funded a new position in the school system focused specifically on health, particularly mental health.

One of the primary resources is in-school counseling from outside resources, according to Tracy Fowler, Chatham County Schools’ director of student services, where counselors will come in from outside groups like Peak Professional to provide counseling and assistance in-school. Fowler said around 200 students throughout the district received that kind of help in both 2016-2017 and 2017-2018.

“For me, there’s been a lot of work — and when I say work, I say community-as-a-whole work — with these issues, especially looking at children,” Fowler said. “There’s been a big push for access to mental health.”

Chatham Charter began an initiative this year called “Knights on a Crusade” to help students focus on positivity. Faculty participated in a mental health first aid workshop and student support services staff have taught lessons on positivity and good relationships in various classrooms.

This kind of focused attention to teens, Brannon says, helps students beyond their emotional state.

“They really perform better in the classroom,” she says. "I can speak to what I’m seeing with kids who are struggling academically and are emotionally dis-regulated. If we put the time in at the forefront, it’s a big difference in what they can handle academically.”

Beyond institutions

Along with treating those who struggle, Mahon says it’s important to kill the stigma that surrounds mental health among those who don’t struggle.

“If you had a broken bone, would somebody say, ‘Just get over it’? No, nobody would say that,” she says. “You may not see what’s going on on the inside, but that doesn’t mean that it isn’t going on.”

She adds that it’s vital to listen to teens struggling and validate their feelings, particularly in serious cases. Mahon jokes that she’s not “PC” – politically correct – and she’s willing to get in the messy stuff.

“Suicide is something we don’t talk about and we need to talk about it,” she says. “People don’t even want to mention the word ‘suicide’ around a kid. The idea is already there. Most of my kids that I’ve seen over the years have thought about suicide once or twice over the years.”

Mahon estimates that around 95 percent of her patients have considered suicide or para-suicidal actions like self-harm.

The work isn’t done in Chatham County. Long and Henzey said the CHA’s results have led them to consider further surveys, particularly into the reasons why teens feel the way they do, and action plans for this issue.

“They’re telling us something through the data,” Long says.

Henzey adds, “Once you figure out the whys, you can figure out the strategies.”

Finding peace

Near the beginning of her eighth grade year, Abigail finally broke down and told her mother. Sitting on her bed, crying, she talked about the depression, the anxiety. Instantly, Jennifer knew what to do. Their family has a history of anxiety and depression, and Samantha, now 22, had similar issues.

Abigail started seeing a therapist and was eventually prescribed sertraline, more commonly known as Zoloft, joining the growing number of people taking anti-depressant medication. According to a study from the CDC, just 1.8 percent of Americans were taking anti-depressants from 1988-1994. That number jumped to 10.7 percent in 2011-2014.

Abigail says it’s helped her “so much.”

Eventually, she decided she wanted to do something more. After talking to Brannon and her mother, Abigail began giving presentations about mental health and shared some of her own story with other classes at Chatham Charter. Jennifer said it made her cry with pride in her daughter.

“That was a wonderful, eye-opening experience for our students,” Brannon says. “What came out of that was a lot of students coming to me and saying, ‘I think I have this, I think I have this.’”

She adds that it allowed for conversations about differentiating between a moment and a continuum of feelings, but meant so much more as far as having students thinking about their feelings and emotions and how they affect them.

Abigail has found new ways to cope. She taught herself how to play the piano and paints and draws. A wall in her bedroom is covered with depictions of some of her favorite music artists — prominent art includes Tyler, the Creator and Selena Gomez, both of whom have publicly discussed their mental health struggles — and photos of friends and family.

How far has she come? Two years ago, Jennifer says, she wouldn’t have sat for a newspaper interview about this, and Abigail readily agrees.

But not all has been roses. While her fellow students have responded well to her presentations, she says adults have not always been supportive.

“It’s really frustrating when people say, ‘Why do you speak about this when you don’t know much about it?’” Abigail says. I’m like, ‘I do know a lot about it.’ They don’t look at your side of the story.

Still, she persists, telling her side of the story to anyone who will listen. And she encourages parents to start that conversation with their teenage children.

“As a teenager, we take a lot of things to heart,” she says. “We think about it and stress over it, and it just consumes us.

“I took a lot of it out on myself. There was just a lot of self-hatred during all of it. I would look in the mirror and be like, ‘I don’t even want to look in the mirror. I’m disgusting.’ That’s what I would think every single time. It’s hard to find coping mechanisms when you feel like no one’s there to help you.

“If anyone has kids or anything, start a conversation about mental health. Bring it up and start talking about it. That’s the easiest way, I’d say.”