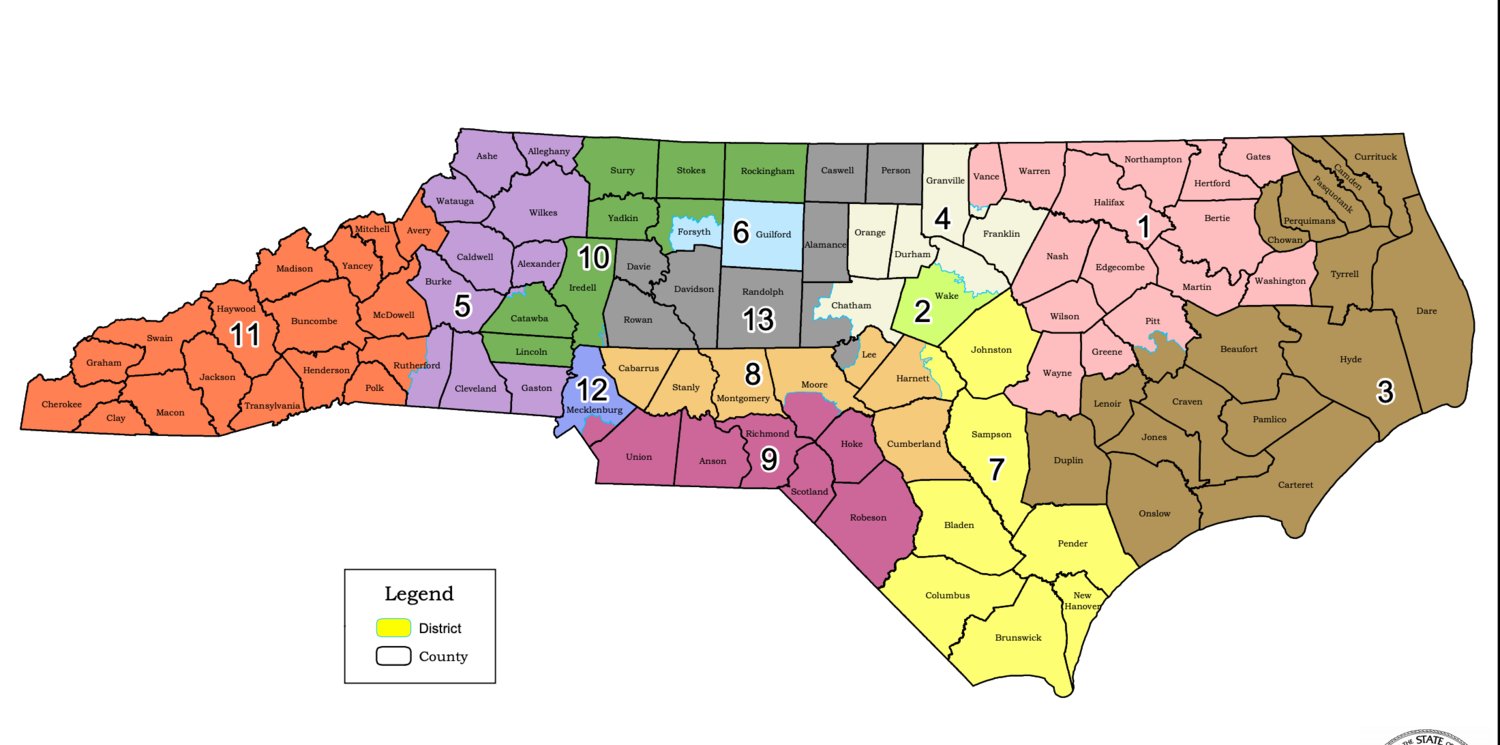

RALEIGH — North Carolina is the country’s most gerrymandered state, and the General Assembly is likely to again promote unjust voting maps during this year’s biennial redistricting, according to election researchers at Princeton University.

Gerrymandering is the illegal practice of manipulating voting districts to favor a political party. It has plagued North Carolina for decades and the problem, members of the Princeton Gerrymandering Project say, is that legislators are endowed with too much unchecked power to create districts that serve the majority party’s political agenda.

“What’s happening in North Carolina right now is a very unique case of opportunity and intent,” said Hannah Wheelen, the team’s senior analyst and project manager. “I think in most states when there’s a slight bit of partisan control, there’s probably a little bit of an intent to use power to draw lines. But in North Carolina, we don’t see a lot of the mechanisms that in other states block it from getting out of control.”

Wheelen is a founding member of the research group, which falls under Princeton’s Electoral Innovations Lab. The team was assembled in 2017 to identify gerrymandering with quantitative data and analysis, and isolate countermeasures that can effectively stifle proliferation of the illegal practice.

“We do a couple of different things,” said Jason Fierman, the group’s communications associate, “provide numbers that prove gerrymandering, draw maps, design tools to help gerrymandered communities, use legal analysis and build networks of activists and organizations in all 50 states.”

Some obvious trends have emerged from the researchers’ nationwide investigation. First, independent commissions tasked with drawing district lines produce the fairest maps. About nine states have “truly independent commissions,” Wheelen said, “and a couple others have something that has some legislative influence, but they don’t have complete control.”

In states where legislators draw maps but the court system has been historically inclined to intervene immediately when gerrymandering is identified, legislators are discouraged from drawing unfair boundaries. And in states where the governor has authority to veto gerrymandered maps, the research group found fewer aberrations.

“But I think in North Carolina we sort of see none of that happening,” Wheelen said, “and we see the legislature having control to get whatever lines they want passed in the next redistricting cycle. And so I think that’s what’s different, that’s what makes North Carolina feel so much worse. And it’s also combined with a history where North Carolina has been able to do this and it’s been part of the politics for so long.”

For example, in 2011, a newly Republican-controlled legislature passed voting districts that were widely decried as unjust and partisan. The issue launched several court cases, the most recent of which concluded just last year. In at least two instances, a panel of judges deemed the districts unconstitutional and required the General Assembly to revise them.

But the issue is not strictly Republican. When Democrats held majority power, they, too, drew unfair districts, according to Rep. Robert Reives II of Goldston, the N.C. House of Representative’s top Democrat. The problem, he says, is that North Carolina’s system would have legislators set aside their personal interests — and that almost never happens.

“When you’re asking elected officials to draw the districts in which they are going to be running, you’re asking them to do something that’s completely counter to human nature,” Reives said. “And on top of that, even if legislators are able to overcome their own inclination to do something that benefits them, you still have to make them believe that everybody else is going to do the same thing, and I just think that doesn’t make sense. Why even put ourselves in that position when you can just have somebody else do it?”

Reives, whose district includes all of Chatham County and part of Durham County, is a primary sponsor of House Bill 437, the “Fair Maps Act,” which would delegate redistricting authority to an independent commission of voters. The bill would promote a more united General Assembly, he says, where legislators are compelled to work for all North Carolinians’ interests and narrow the political divide.

“Your best democracies and your best governments are governments that have to govern somewhat from the middle,” Reives said. “Governments that govern from either side of the political spectrum always tend to be your worst governments. And if you gerrymander, you’re encouraging government from the edges.”

The Princeton team agrees. HB437 would introduce a system similar to what other states — such as Arizona, usually a Republican stronghold, and California, a Democratic bastion since the 1990s — have used to minimize gerrymandering.

“Our feeling is that fair process is really what leads to fair maps,” Wheelen said, “and an independent redistricting commission is what I would call really the gold standard to redistricting reform right now.”

But the bill is unlikely to pass. An independent commission never suits the majority party’s interests, Reives says. In North Carolina’s history, both Democrats and Republicans have proposed bills to introduce an independent commission when each was part of the minority party. The majority always strikes them down.

To enact any lasting change, Wheelen says, voters would first have to voice displeasure with the current system.

“I don’t think the legislators are going to do anything unless they’re pushed, and we’re hoping that citizens and citizen groups get a hold of this data, and once it becomes so clear that the maps that are being proposed are clear gerrymanders, I hope that there’s a push back,” she said. “I think

legislators have been able to pass these really bad gerrymanders because there isn’t really a price to pay for doing it. And so if they for once feel like their constituents are angry, and they might possibly not get reelected if they push such a bad map through, they might respond.”

To Reives, change cannot happen until voters understand that gerrymandering affects everything legislators are able to accomplish. Hot-button issues won’t be fairly resolved, he said, until the General Assembly accurately reflects North Carolina’s constituency.

“I think people just aren’t aware how important the issue is,” Reives said. “When I listen to voters, there’s always one or two issues that just makes them burn, either in a good way or a bad way. But nobody seems to realize that every issue that you care about is affected by gerrymandering — every single issue. And if they understood that, it would be everybody’s number one issue. The number one issue wouldn’t be their passion issue; the number one issue would be gerrymandering, and they’d say, ‘Hey, get these districts fixed so that we can have a government that’s more responsive to my needs.’”

Reporter D. Lars Dolder can be reached at dldolder@chathamnr.com and on Twitter @dldolder.