The Chatham Community Library and Chatham’s Community Remembrance Coalition will commemorate Black History Month by co-sponsoring a virtual lecture about the contributions of Chatham’s free people of color during the Revolutionary War.

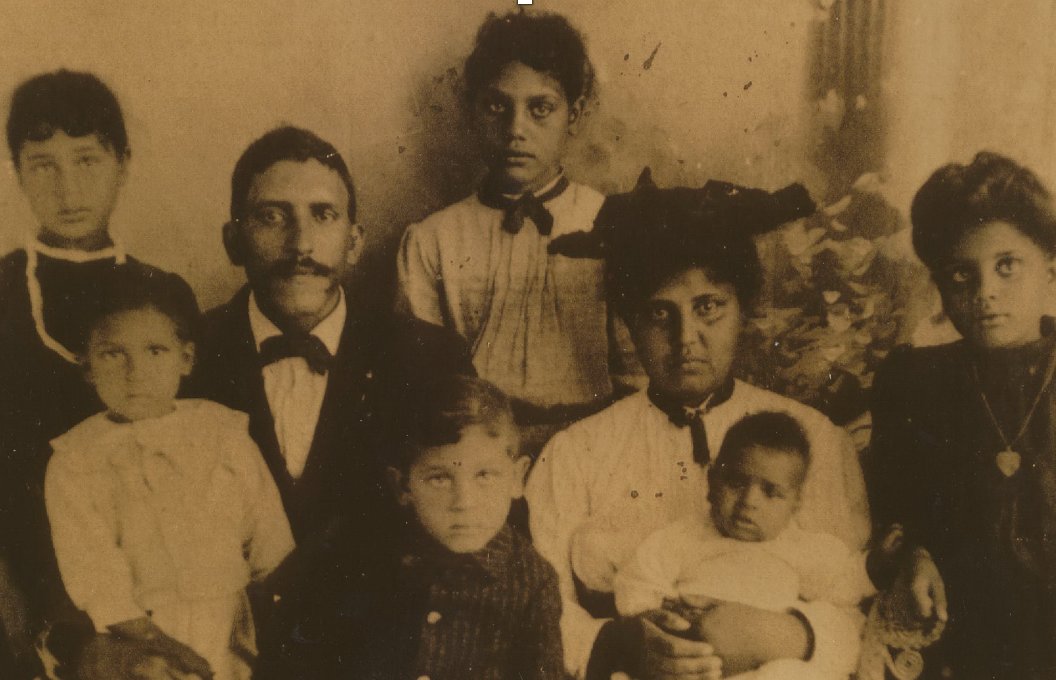

Given by David Morrow, a lawyer and writer based in California, the lecture — “Patriots of Color in Chatham County: Untold Stories” — will highlight his genealogical research that began with his own family tree, and expanded to over 6,000 names across multiple states and countries.

The program is free and will be held via Zoom from 2 to 3:30 p.m. on Saturday, Feb. 19. To attend, register here.

Morrow was the first in his family to prove lineage to a Black patriot, as well as the first Black member of the Los Angeles Chapter of the Society of the Sons of the American Revolution (SAR), where he now serves as secretary for the executive board. He is also the co-founder of the Facebook group “Native & Free People of Color of Alamance, Chatham, Caswell, Granville, and Orange Counties in North Carolina,” which has over 600 members.

Originally from Washington, D.C., Morrow now lives in Los Angeles with his wife, Erica and their son David III. In addition to SAR, he is a member of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, the Bachelor-Benedict Club of Washington, D.C., and the Diversity Working Group for the National Genealogical Society.

Morrow has been a speaker at multiple national conferences on issues of diversity in the legal profession, and was the inaugural director of the Men of Color Project for the American Bar Association. He has appeared on numerous 40 Under 40 lists with the National Bar Association and the Business Journal and was honored by the National Bar Association in 2013 as the Young Lawyer of the Year.

This week, the News + Record spoke with him about his research on patriots of color and his hopes for his upcoming Chatham presentation. The following interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

David Morrow: The library is setting it up and asked me to speak. My family’s from North Carolina — my parents were born there. I actually wasn’t, I was born on a military base in Michigan, but most of my family’s still in North Carolina.

Chatham County [Community] Library had reached out, I told them about my research — I had attended one of their programs and I posed some questions and then they Googled me. Then I was like, “I’d love to do a presentation on patriots of color during Black History Month.” So that’s kind of how it all came about.

Growing up, my family always talked about their deep roots in North Carolina, and so I was really aware of family history — probably more so than the average African American out there — but I didn’t know the deep history that I ended up uncovering. My background is I’m a lawyer, I’m based out here in Los Angeles, but I am also a genealogist on the side. That’s one of my passion projects. I started that work back in 2007 — I knew that I had a unique family history, and so I wanted to just learn more about that and I uncovered even more than I was expecting.

That unique part was just about being descended from African Americans who were never enslaved, but living in North Carolina. Of the slave-holding states, North Carolina had, I think, the second- or third-largest free population of people of color before 1860. On my dad’s side of the family, multiple family lines of mine were from these different communities that were racially mixed — African Americans, Native American origin — and so I wanted to learn more about that. In that process, I learned about the number of people that were in my family tree, and from that particular community in Chatham County who fought in the Revolutionary War.

Being a military kid, I’ve always been fascinated with military conflicts, one being the Civil War, which is always interesting, but then the Revolutionary War, which is interesting, too. For me, I didn’t realize the extent that African Americans had played in that war. I think most people make false assumptions that all Black people were enslaved or that no one fought in that war conflict, when in fact, there were thousands of black soldiers commissioned then. What’s unique about North Carolina, and particularly Chatham County, is that there were at least 30-something black patriots in that community.

So as I was uncovering the four in my tree, because there’s about 30-plus families that all kind of married each other over a 200-plus year period, there were other folks in the community that also fought for independence. I’ve been trying to document and research those individuals and their families and share that with a lot of their descendants, who still live in Chatham, Siler City, and then Alamance County and Orange County — between those three right there, that’s pretty much where I would say 75% of my dad’s family still lives to this day, and they’ve been there since the mid-1700s.

I view this as untold history that’s pertinent to those still living in Chatham, and is just interesting about a certain community’s contribution to the founding of this nation. And then I like to share a little bit about the lives in which they lived during that time period because they walked a line, right? If you were a free person of color at the time, you had to walk around with papers all the time that said you were free or you could be thrown into bondage. So they had their white neighbors, they had the enslaved and then there was them, in the middle trying to figure it out.

African American history and race in general, especially in the South, is very complex and it’s not just one story.

But back then, I think it was unique for North Carolina, and particularly Chatham — the largest counties that had free people of color were down in Robeson and Granville and then number three was the Chatham, Alamance, Orange area. There’s no historical marker about this community. There’s churches that still exist right now that were built by this community, one being Burnett’s Chapel — there’s a lot of people buried out there, pretty much huge chunks of my family tree buried out there somewhere. Many of these families were landowners, and so there’s still parts of it being lived on by their descendants. So you have a continuous land ownership story for African Americans that reaches back almost 200 years in North Carolina, which also is very unique.

What will the event itself look like?

It will be me doing a virtual presentation from the West Coast. I’ll dive into my history and my connections to the community, and highlight these 32 men who fought in the Revolutionary War. I’ll go into some detail on certain ones — which regiments they fought in, which battles and where their descendants are right now, which is they’re all over that area in North Carolina.

Part of this is also important for me because, through my research, I’ve joined the Sons of the American Revolution (SAR), which is a Genealogical Society similar to the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). My hope is that this research could help other descendants of this community apply for membership into these organizations, because I think again, there’s a false assumption about African Americans in history in general. These organizations can have Black members; we fit the criteria.

Because it goes to the very heart of who’s American. There’s this whole thing when it comes to race, as if somehow we’re not part of this country’s origin, or current state, and the contributions that we’ve done to create the current version of America.

So I see these types of stories, and I see them in my own family tree, it’s like, “Oh, I’m clearly American. I mean, I’m definitely of African origin, but my family’s been here before America was America and during and after it became America, so what else could I be?” In the civil rights era, during the protest movement, signs would say, “Go back to Africa,” as if we weren’t already here. It’s such a funny thing to think, well, what does it mean to be American? Does it mean to only be white? Well actually, the fabric has been diverse from its inception.

I see these stories, especially in history from years ago. We learn about George Washington or Thomas Jefferson, but maybe we should learn more about Crispus Attucks, who was the first person to actually die in the war conflict, and he was a Black man. And then understanding that everyone has a piece of this history. It’s not just for certain people that can lay claim to our founding fathers or to what occurred 200-plus years ago.

What I’ll add on to that about the organization is that SAR has been super welcoming to me. I actually spoke at the California officers meeting out here in Anaheim about a week ago. I actually sit on the board for Los Angeles; I’m the secretary on the executive board.

I haven’t felt as if somehow I wasn’t wanted — I just think that for these organizations, the level of proof you have to show is sometimes hard to demonstrate if you’re a Black person, and the documentation may not be all that sound, or may not be there. You know, old family stories don’t count, you have to have an actual written record to demonstrate your connection to that period of time to join these types of organizations — that’s very easy for the white population. For African Americans, one, I think it’s only about 25% of Black people descend from those that weren’t slaves, so the vast majority of most African Americans’ trees are going to be that of enslaved people, which means you cannot go back before 1865 and the Civil War — that’s where your tree will end. For that other percentage, I think if you can demonstrate your connection to that period of history, then you should join these organizations and change the narrative.

They learn something about the area that they did not know. History is history because people write about it, but if you don’t write about it and you don’t remember it, how can it be actual history? So for me, it’s important to share this history, the documentation to say, “Hey, this is what Chatham County did during that time period. This is what the African American community contributed to the nation’s inception, and let’s not forget that.” Let’s not forget about the people in our own community. Let’s not forget about the people who are literally the families that are still living down the street from each other.

One goal is just education and making sure people remember this; the second one is, I would like to do a historical marker. I think this comes to that level where I think this county should lay claim to 30 individuals who fought in the war effort that were people of color. So those are my goals: one is education, a historical marker in Chatham somewhere near Siler City, and then to increase the roles of members of this community within SAR and DAR.

Reporter Hannah McClellan can be reached at hannah@chathamnr.com or on Twitter at @HannerMcClellan.