Note to readers: This is the first of a two-part story about the legacy of Chatham County’s lynching victims and an effort by some local residents to memorialize them.

1: The last lynching

Late in the evening of Sept. 16, 1921, a Friday in the waning days of a long North Carolina summer, a young Chatham County woman by the name of Gertrude Stone awakened to see a man standing over her bed.

Gertrude, 17, lived at home with her parents on Farrington Road in New Hope Township, a few miles outside of Pittsboro. Her father, Walter, was away from home that night, hunting with friends, and at first Gertrude thought the person in her bedroom might be her 12-year-old brother, Ernest.

Upon realizing it wasn’t, she screamed.

The sound startled the intruder — a black man who happened to live with his family on the same road as the Stones, on a farm, ironically, the young man’s father purchased from Walter Stone’s brother.

The black man fled.

“Miss Stone and her mother immediately gave the alarm, but the negro had disappeared, and no trace of him could be found,” read an account of the incident in the Sept. 19, 1921, edition of The Charlotte Observer.

The “negro” was Eugene Daniel. Within 30 hours, he’d be dead.

Various newspaper reports eventually spelled out the timeline of what transpired: upon Walter Stone’s return home early Saturday morning, Pittsboro police were alerted. Bloodhounds from Raeford and handlers were summoned, tracking Eugene from the Stone home to a hiding place. He was captured, and in short order was said to have readily confessed to the crimes for which he was charged: trespassing and attempted rape.

He was taken to the Pittsboro jail and placed in a locked cell. Sometime that night, or very early Sunday morning — accounts differ — some 50 men from New Hope Township, an area which Jordan Lake, not in existence at the time, now bisects, stormed the jail. After three failed attempts, one or more of the men were able to wrest the jail’s keys from jailer H.W. Taylor; one news account says Taylor simply laid the keys down on a window sill and walked away.

In any event, Eugene’s cell was unlocked and the prisoner was hustled outside. He was taken some five miles east of Pittsboro to an area near what was then called Moore’s Bridge, along the old Raleigh road. Walter Stone, according to reports, was among those who made that trip.

It was there, at a site now submerged under the waters of Jordan Lake, that punishment to Eugene was meted out: the perpetrators threw a tire chain over what was described in one newspaper account as “a convenient limb,” then wrapped it around Eugene’s neck, and hoisted him into the air.

As Eugene began to suffocate, his legs thrashing as his body instinctively fought for life, some of the men there made his justice complete, pulling out rifles and revolvers and firing at him.

The battered, bleeding body hung from that convenient limb until after sunrise. By mid-Sunday morning, as the day began to warm and news of the hanging spread, more than 1,000 people had made the trek to the scene to catch a view.

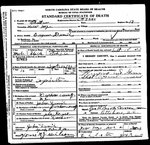

Finally, sometime before noon, Chatham County’s coroner, George H. Brooks, arrived to claim the body. Later that day, on Eugene’s death certificate, Brooks scrawled in the official cause of the young man’s demise on the paper.

“Hanging and Gun Shot wound,” he wrote. “Lynched by mob.”

Eugene Daniel was eight days past his 16th birthday.

The date of death was listed as Sept. 18, 1921. Eugene was the sixth — and last — lynching victim recorded in Chatham County history. The very first recorded in North Carolina — in early 1865, of an “unknown black male” — also occurred in Chatham County, according to an appendix of lynchings published in historian Vann Newkirk’s 2009 book, Lynching in North Carolina: A History, 1865-1941.

The state’s last, Robert Melker of Wilkes County, was hanged on April 13, 1941.

His crime?

“Arguing with a white man,” according to Newkirk’s book.

Across North Carolina, only one other county had more lynchings than Chatham County did — New Hanover, with 22, many associated with race riots there in 1898 — and only two counties, Granville and Rowan, had as many.

All told, in the years between 1865 and 1941, by most accounts, there were 168 victims of lynching in North Carolina. A significant majority of victims were black men, and most were lynched without the benefit of a trial — killed, typically, by vigilante groups of white men after real or perceived crimes, and usually by hanging. Twenty of the lynching victims were white — 19 men and a single woman, Ella May Wiggins of Gaston County, a union organizer who was shot and killed in 1929 while leading a strike of the Loray Mill in Gastonia.

In Chatham County, Eugene Daniel — mistakenly called “Ernest” or “Ernest Daniels” in some records — was the state’s 157th victim.

Today, few of the 168 are remembered or memorialized or recognized in any official way, relegated instead to a stain on the legacy of their home counties and of the state, a part of history that many people would prefer to forget.

Bob Pearson, though, isn’t like most people.

Pearson, who retired to Chatham County in 2015 after a long career in the American Foreign Service — where he worked mostly overseas as an attorney and diplomat, followed by six years with an international humanitarian group involved in reconciliation and negotiation work — is leading the effort here to memorialize the six victims: Daniel, Richard Cotton, Harriet Finch, Jerry Finch, John Pattisall and Lee Tyson. He’s been joined in the effort by a growing group of supporters — white and black alike, and including members of both of Chatham’s NAACP branches — and what he’s sparked is taking root in Chatham, just like similar efforts around the region of the state and the south. What the memorial might consist of, exactly, is still being discussed; a 10-page proposal Pearson drafted outlines several options, but it would certainly involve telling the stories of those lynchings.

It’s in the telling of those stories that he and other community leaders hope healing will take place.

2: ‘The consequences of history’

W. Robert Pearson is 76 years old. He bears the upright demeanor and thoughtful countenance you might expect from a Southern-bred attorney whose career has taken him all over the world. Pearson has lived and worked in five different states and six countries outside the U.S., and he served under six presidents and 11 secretaries of state. His work has taken him to more than 50 countries, but retirement brought him to Chatham County.

Today he lives in Fearrington Village with his wife of 44 years, Maggie, a Pennsylvania native whose family roots are in New Orleans. It’s a far cry from some of the other places he’s lived — Japan, China, New Zealand, Belgium, France, Turkey — but not that different from where he grew up, on a family farm in western Tennessee.

Pearson describes his childhood as “a traditional Southern upbringing.” His formative years on the farm and in college in the South coincided with those of the Civil Rights struggle, making him a witness to change.

“I was affected by it,” he states plainly.

In the spring of 1968, Pearson was in law school at the University of Virginia when Martin Luther King Jr. was gunned down by an assassin in Memphis. That event, he says, triggered a simple notion in his mind: there has to be a way to solve problems without violence.

Throughout his career, that belief continued to be reinforced — as were his views on the pain inflicted by the mindset that grew out of white supremacy.

“As a U.S. diplomat I was constantly reminded how the race issue damaged my country overseas and helped our enemies,” he says. “I also knew from my work on reconciliation how hiding truth blocks understanding; when we know the truth, it does set us free to see things in a different light.”

Truth, and history, are clearly important to him. Pearson traces his Southern lineage back more than 300 years; two great-grandfathers were there at Bennett Place in Durham on April 26, 1865, part of the last surrender of a major Confederate army in the Civil War.

And it was truth and history that stirred something inside him when he began working on an international service curriculum with N.C. Central University faculty members after his retirement. As part of his research, he came across Civil Rights attorney Bryan Stevenson’s best-selling book, “Just Mercy” — which chronicles Stevenson’s landmark work on behalf of wrongly condemned people of color and a broken judicial system, and is the focus of a movie adaptation releasing on Christmas Day this year — and learned about the work he was doing through the Equal Justice Initiative.

The EJI, a nonprofit organization based in Montgomery, Alabama, challenges poverty and racial injustice and advocates for equal treatment in the U.S. criminal justice system. It, and its supporters, also spearheaded the creation of The Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice — both in Montgomery. The museum addresses the post-slavery treatment of African Americans by whites, while the memorial serves to call attention to the more than 4,000 victims of terror lynchings of blacks in the U.S.

In reading about the memorial, Pearson learned that part of it consists of more than 800 corten steel monuments, one for each county in the United States where a racial terror lynching took place. Engraved on columns are the names of victims, but in an adjacent field are identical monuments — waiting to be claimed and installed in the counties they represent. So far, more than 300 counties have launched efforts to create local memorials and claim one of the monuments.

Curious, Pearson researched his new home county and learned about the Eugene Daniel lynching — and Chatham’s five others — and the idea fomented in his mind: why not have a memorial to those six victims?

A lifetime member of the NAACP in Maryland, Pearson reached out in Chatham — to the county’s historical association and museum and to its two NAACP branches and to others he thought might have an interest.

“I told them what I had in mind,” he says, “and got the OK to pursue it.”

3: ‘…a history that shouldn’t be hidden’

That’s the “how” of the genesis of Pearson’s work. The bigger question, of course, is: why?

To him, it’s hidden history.

“It’s history that has consequences down to today,” he said, “and therefore a history that should be told. It’s a history that shouldn’t be hidden. I’m not trying to blame anyone for it, but I’m interested in it because people don’t know about it. Knowing will cause them to think differently.”

As he reflects, thoughtfully, on the experiences he had growing up in the South, and the experiences of people he knew, he speaks about what he calls two self-evident truths.

First, that people who have little or no influence — those with few resources or little in the way of status — are more likely to be victims in society. And second: people who dominate the political system are more likely to be the ones who get to write history.

Which is why, he believes, so much of the history of lynchings in the years between Reconstruction and Jim Crow has been forgotten.

So why start talking now?

It’s not just about the act and the crime of lynching, he says, but the predilections of the era of lynching that are still prevalent. Support for federal anti-lynching legislation and progress in the Civil Rights-era struggle largely ended the public spectacle of lynching in the early 1950s, but certain things, Pearson says, haven’t changed.

Lynching, he said, is “the graphic image of white supremacy and white domination of the Jim Crow period. It’s that giant rock that rolled down the hill and crushed everything in terms of rights for African Americans, and it left a legacy.”

That legacy, he explains, isn’t just an ugly, tarnished past. Lynching, he says, created a culture that made it normal and acceptable not to give blacks equal rights.

EJI’s Stevenson, in the foreword to Sherrilyn A. Ifill’s 2009 book, On the Courthouse Lawn: Confronting the Legacy of Lynching in the 21st Century, wrote that nothing in this era “was more harrowing and traumatizing than lynching.”

“The lynchings of African Americans was racial terrorism,” he wrote. “It forced six million black people to flee the American South as refugees to the North and West. It is this lethal violence that shaped the demographic geography of our nation today. Lynching was that violent tactic that enforced Jim Crow in the South and, as the great Ida B. Wells argued, it became our national crime.”

For decades, Stevenson writes, “black people were hanged, tortured, drowned, shot, mutilated, and burned at the stake. The perpetrators of this violence took pride in their terrorism. These American terrorists were celebrated by their communities, who frequently came out with their children to cheer them on. They created a legacy of violent resistance to racial equality that still infects our nation today and poses a continuing threat to equality and opportunity for millions of people of color. That the terrifying violence of lynching would sometimes happen on the courthouse lawn with law enforcement and state and federal governments watching silently is a critical part of the story…”

Asked to explain from his own perspective, Pearson — who is white — launches into a soliloquy about the aftermath, the resultant effects and the “raw deal” people of color got in the lynching and post-lynching era. The Housing Act of 1934. The Social Security Act of 1935. The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. The GI Bill of Rights of 1944. The war on drugs, which was launched in 1971. Pearson can detail, and cites from memory, how each had an unintended — or in some cases, intended — consequence, consequences which, combined, created an “unlevel playing field” and benefited whites in ways that specifically worked against blacks.

Today, he’ll remind you, we’re living in a nation where blacks are arrested and incarcerated at rates five times those of whites, and where the average net worth of white households in the U.S. is 13 times the average of blacks. African Americans and whites use drugs at similar rates, but the imprisonment rate of African Americans for drug charges is almost 6 times that of whites.

So who does Pearson blame?

No one.

“I’m not trying to place blame here,” he says again, “but history has to be told so people can appreciate it.”

And what can they learn?

Recognition. Acceptance, he says. A new basis for moving forward. Reconciliation.

Pearson sees Chatham County as “a special place with a bright future of growth coming.” Its major assets, he says, include a “very respected” county government, superb law enforcement and organizations “interested in having the county go forward.” And if Chatham residents want a county of which they can be proud — one that will attract business and people from other parts of the country — “we need to be able to say that we have no problem embracing our history.”

If you know it, he says, it makes you think differently.

4: ‘Don’t rock the boat’

But the effort hasn’t been without its doubters. Some tell Pearson to forget it, that lynchings are “old history,” and that there’s no need to bring up the subject. No one alive today in Chatham County lynched anyone, he acknowledges, and he understands the reluctance to re-tell stories that are hard to hear.

“‘Don’t rock the boat,’ they say,” he says “‘Time will cure all. We’re all doing OK now.’ Quite honestly, this is the kind of argument heard at every stage of the Civil Rights era. That just doesn’t stand up as any kind of reason.”

Another truth, he says, is this: the more complicated a situation, the longer it takes to resolve — “and more effort goes into resolving it.” Thus his work to gather groups to put in the time and effort, with patience and persistence, to “take this step.”

“It’s not designed to produce conflict,” he explains. “It’s designed to recognize history and truths and to move forward.”

The work, he believes, would broaden the process of understanding in the county about our common history. It would also foster a broader spirit of reconciliation within the county as its citizens work hard for a brighter future.

“With much new growth anticipated and many new residents coming to the county,” he said, “it is a good time to add momentum.”

And how would a memorial help reconciliation?

“We can only see eye-to-eye when we all share the same history,” Pearson says. “In the South, many people attach importance to what happened between 1860 and 1865. Is it not important also to know and understand what happened afterward and how events then affect our society today? Those events were a nearly impossible barrier to social and economic progress for nearly 40 percent of the South’s 1860 population until segregation ended almost a 100 years later.”

Pearson says that thanks to progress in recent decades, “supported in very large part by white citizens,” we can now examine what actually happened.

“Reconciliation doesn’t require that everyone completely agree, but it lets everyone understand what happened and think about its effects down through the years,” he says. “In my experience, it always leads to progress based on a shared knowledge.”

And it’s not about blaming those who did the lynching, but about explaining the aftermath.

“This effort is not aimed against the white community or white citizens, who, as I have said, have been very supportive of progress in the South and in this county,” he says. “It is for something, not against something. Chatham County has a bright future. Reconciliation will help us focus on how to make the most of the potential of our young people, not ‘export’ them to other cities and states, create the new jobs we need, and the business opportunities we want to see.”

But for some, while reconciliation is a worthy goal, the answer about memorializing lynching victims isn’t quite so clear. Jim Crawford, a Chatham County commissioner and former history professor — and part of the majority on the county’s board who just recently voted, in essence, to remove the “Our Confederate Heroes” monument from the Historic Courthouse lawn in Pittsboro — says it must come with a discussion about reconciliation.

“I am not comfortable with the only representation being their victimhood,” he says of a potential memorial. “In other words, we’re putting up another monument to white supremacy, except it’s just our attempt to stand it up on its head and then negate it. And personally, I’m not terribly comfortable with that. Do you know what I mean?”

Crawford thinks that by trying to teach a broader lesson about the horrors and the legacy of lynching, “really all we’re doing is reminding everyone of white supremacy’s power.” In doing so, he says, a day might come where white supremacists visit the memorial and see it as “a triumph.”

True reconciliation, Crawford says, is a “discussion between the aggrieved parties,” similar to the Truth in Reconciliation Commission work that occurred in apartheid-era South Africa — an ideal solution to what ails the psyche and the wounds created by lynching and white supremacy.

Despite these events, Pearson points out, the black community in Chatham County kept rising and kept succeeding. They founded churches, schools, civic organizations, saved their earnings, bought land, built homes, kept their children in school and sent them to college when they could.

“Theirs is a history of triumph over difficult odds for nearly 100 years — between 1865 and the Civil Rights Voting Act of 1965,” Pearson said. “African Americans have risen to prominence and leadership in our community. In the last half-century, white citizens of Chatham County as well have worked hard and generously to support the black community in many important ways.”

Still, Pearson, and Pittsboro Mayor Cindy Perry — who, like Pearson, is an attorney and has also worked in the field of reconciliation — agree with Crawford that there’s still room for more progress on the question of reconciliation.

Reconciliation, Perry says, “is a beautiful idea.” But she’s adamant that it won’t come “just from putting up a plaque or a symbol of the dirt that was accumulated from where people were lynched.”

“What it’s going to take is a real series of communication,” she says, “where we sit at the same table. It’s going to take a real serious sitting down together and listening to each other. My gosh, that’s important.”

Pearson, who’s done hard work in reconciliation during his career, thinks some kind of a memorial will open the door for it in Chatham County.

He raises the obvious question:

“Are we supposed to continue to pretend this history didn’t happen because an extremist will defend it?” he asks.

Then answers: “If so, then we seem to be doing exactly what the extremists want done — hide it and act like it never happened,” he says. “That will just continue the damage that has already been done. If life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness mean anything, they mean that every citizen is entitled to these unalienable rights. It’s a good thing to be on that side of history, and I believe the overwhelming majority of the Chatham County community agrees.”

Next week, in part 2, a closer look at the Eugene Daniel case, more on the legacy of lynching, and a discussion with the leadership of Chatham County’s NAACP chapters and others about this effort — and where in this discussion the Confederate statue in Pittsboro comes into play.