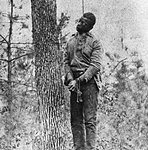

Editor’s note: This is the second of a two-part story examining the effort of some Chatham residents to memorialize the victims of the county’s racial terror lynchings. A photograph depicting an 1899 lynching is shown on page A8. Readers may find the image disturbing.

1: Crime and punishment

When Eugene Daniel, Chatham County’s last lynching victim, was captured by Pittsboro police on Sept. 17, 1921, death by hanging — “lynched by mob” was what was written on his death certificate — came relatively quickly, within 12 hours or so of his apprehension.

“The negro apparently was not taken before his intended victim for identification,” read an account of the events in the Sept. 19, 1921, edition of The Charlotte Observer, “but his alleged confession to officers had become public property in Pittsboro.” The newspaper said that confession — to the crimes of trespassing and attempted rape — was “satisfactory evidence” of Daniel’s guilt.

Daniel’s killing followed a fairly typical pattern of the 4,000 or more racial terror lynchings in the South and elsewhere in the period between Reconstruction and the Civil Rights era: a crime or slight is committed, usually by a black man; an accusation is leveled; at some point a rush to judgment is made, often with little or no proof of the accused’s guilt, often ending in torture or death.

In stepping uninvited into the bedroom of a white woman, Eugene Daniel breached community standards, an act “sufficient to ignite the spark of mob violence,” as one newspaper reported about the incident. In the Jim Crow South, lynching was a predictable ending to that kind of story.

Understanding why that’s the case is part of the point of the effort of a group of Chatham County residents who seek to do what more than 300 others counties in the United States are doing: publicly acknowledging, with a memorial of some kind, those lynchings — but also acknowledging the mores of the society that, at that time, made the practice acceptable, and how those acts reverberate today.

For Bob Pearson, a Fearrington Village resident who’s played a major role in the effort in Chatham, the point of a memorial isn’t to spotlight the ugly incidents, blame the perpetrators or create a monument that would serve merely as a stopping point for visitors or another in a long list of historical markers. Rather, Pearson sees it as providing a teaching opportunity about history and creating a framework of knowledge for the community. From there, reconciliation — a community-wide commitment to building cross-cultural relationships and the pursuit of forgiveness, love and understanding — can really occur. A shared history, he and others say; a shared understanding, a shared way forward. True healing.

It starts, though, with history.

“At the moment there is no comprehensive record of this part of the history of Chatham County,” says Pearson, 76, a retired attorney and diplomat. “While the history of the white community is well known, the history of the black community after 1865 and during segregation remains largely unknown. For those who want to understand how the country was governed and how the communities, black and white, led their lives, this is important.”

Pearson emphasizes what should be an obvious truth, but isn’t — that tens of thousands of citizens in this county, black and white, see their history and the history of the South differently. If there’s a shared understanding of those histories, he says, of walking in one another’s shoes, the legacy those histories carry creates a clearer picture of how we’ve arrived at where we are now.

“For everyone,” he says, “it is important that the next generation know this history and be inspired and determined to build a future that recognizes what happens when the protection of the law and the Constitution is not provided equally to every person.”

That’s part of the goal of the effort that Pearson and a growing group of others — some white, like Pearson, and some black — have embarked upon. Talk to Pearson for any length of time and you’re bound to hear him say, “If you know history, you think differently about it.”

2. Lessons from history

That history, the story of a time period in the South, is a story Chatham County Commissioner Jim Crawford has told often. Crawford, a former college professor, earned history degrees from UNC-Chapel Hill and Penn State, as well as a doctorate in philosophy. Hearing him speak, sitting on an unfolded wooden chair inside the coolness of Chatham Cidery in Pittsboro, where he creates hard apple cider, is like sitting in an advanced history class. Crawford has taught before about the subject of lynching, a practice which began as America began to settle itself after the Civil War.

“There seemed to be progress for African American rights being respected, and then slowly, slowly it begins to erode roughly after 1876,” he says. “People who are familiar with their history know the story. So, what’s the significance? It’s a story of contestation, of white supremacy being challenged; and, in this instance, white supremacy saying, ‘You will obey, and you do not have the same rights under the law.’

“The whole problem with the lynching” — here Crawford speaks of the killings of Harriet Finch, Jerry Finch, John Pattisall and Lee Tyson in Pittsboro on Sept. 30, 1885, four of Chatham’s six lynchings — “apart from the murder itself, is that nobody got due process and that, looking back, we can’t say with any degree of certainty whether or not those individuals were really involved in that crime in the way the indictment would’ve said.”

The injustice of lynching, say those who’ve studied it, was made palpable by an attitude, a belief system that, according to Crawford, has “a long, historical power structure where it was built by white supremacists for white supremacists.”

He explains: “So white supremacy is not just a personal belief system, right? It’s not a mere prejudice that you have or I have against certain folks, or they have against us. This is a dehumanization of other groups by a group that has a preponderance of power, and then all of the structures of power by which that dominance is protected, maintained and perpetuated. So that’s what we’re dealing with.”

It’s not, Crawford says, a matter of saying, “You’re a racist; you need to fix yourself, and then everything’ll be fine.”

Rather, he says, there’s a structure, and it goes from place to place — beginning with the “original white supremacy is European settlers and Native Americans.”

He asks: “You might say, ‘Where does that leave white supremacy, because they’re white?’ Well, they’re quite pink actually — and it just shows you that it’s a variability thing and it really has nothing to do with what people look like and who they are biologically, their phenotype. It’s about how they stand in the power threshold.”

It’s about marginalization, he says.

The discussion and the effort come at a pivotal time for Chatham County, for obvious reasons — look no further, for example, than Saturday’s simultaneous protests around the Our Confederate Heroes monument at the historic courthouse in Pittsboro, attended by two groups with very different beliefs and attitudes about the statue.

As for Pearson, you’d be hard-pressed not to forgive him for not wanting to compare this effort to the effort and desires of those who strongly favor keeping the statue outside the courthouse — the very same statue that Eugene Daniel likely caught a glimpse of as he was busted out of the town’s jail that late-summer night in 1921, and the same statue that Crawford (who has been vilified and pilloried on social media of late) and three fellow commissioners have voted, essentially, to have removed.

Pearson and others working on the project acknowledge the tendencies of casual observers to see a link, but Pearson feels the statue and its future are legal issues and not related at all to the question of Chatham’s lynching legacy and an effort to memorialize them.

“What we’re trying to do is much broader than that,” Pearson says. “We’re just trying to show a history in the county that hasn’t been known before in an effort to bring everybody an understanding of that history. That will allow for a better degree of reconciliation and a determination to make the community better. It’s an opportunity to make things better for everyone.”

But first, there’s the telling, and the acknowledgment, of history and its ramifications.

3. ‘State-sanctioned terrorism’

Echoing Crawford’s lesson, an essay published last month on the Politics North Carolina website — written in response to recent articles in The Atlantic magazine (about the transfer of millions of acres of land from African-Americans to corporations in Mississippi) and another article in The New Yorker (about a similar story from eastern North Carolina) — said that even though our nation passed laws in the 1960s that ended Jim Crow, “we never fully acknowledged our history or paid for our crimes.”

“Instead,” writes Thomas Mills, PoliticsNC.com’s founder and publisher, “we continue to bury the past, holding no one accountable and telling black Americans that they were now free to pursue their dreams, ignoring massive obstacles in their way. State-imposed poverty dogged families in both inner cities and the rural South.”

Mills goes on to write that history books “glossed over the damage that Jim Crow really caused,” and describes lynching as “state-sanctioned terrorism” that “denied African-Americans their basic rights for a century after the end of slavery.”

He quotes former George W. Bush speechwriter Michael Gerson, who, in another recent essay, declared racism as “the fire that left our country horribly disfigured.”

A half-century after the successes of the Civil Rights Movement, those who recognize the legacy of lynching and Jim Crow “want an acknowledgment that the horrors of slavery didn’t end with emancipation.

“They want our history known,” Mills writes.

That’s been Pearson’s argument as well.

“Chatham County will be able to learn about our shared history and recognize how the past has held back our whole community from achieving all that could have made greater progress,” Pearson says. “Everyone will better understand the importance of equal treatment before the law and look forward with conviction to what the future can hold for all our citizens. An understanding of our shared history should give all our citizens increased respect for each other, our experiences then and our way forward now. The next generation will have a firm foundation on which to see and build the future.”

His supporters agree. Mary Nettles, the president of the East Chatham branch of the NAACP, says, simply, “It’s history.”

And Larry Brooks, the president of the West Chatham branch, says the injustices of history are still relevant today.

“What makes it important is the fact that this was injustice that was done to people,” he says. “It was not equal justice. It was injustice. They were hung because of what people felt, whether it was part of racism or part of what they thought was legal, but it was not legal. It was not by law. It was not a situation where these people had fair hearings.”

Brooks isn’t insisting upon having “a program every year” to remember the victims, because he understands that’s not the point.

“But if you just do something so that people can see and remember,” he says. “You have to keep people aware of stuff. Even if you put up the signs that Bob talks about you’re not putting them up for hatred; you’re putting them up for remembrance, that people should do the right thing.”

4. ‘It was a terrible time’

Yet, telling that history and illustrating its ramifications with some kind of a memorial remains a layered issue, at once simple and complex.

Talk with another member of the East Chatham NAACP, Pittsboro Mayor Cindy Perry, about what she thinks about the effort and it’s obvious she recognizes the complexity of the question. For her, that complexity is exacerbated because of the core of who she is: as a Quaker, a member of the NAACP, a politician, an attorney, and as someone who, like Pearson, has worked in the field of reconciliation.

She’s quick to acknowledge that from a jurisdictional standpoint, she has the “luxury” of sitting on the sidelines to watch and listen to the discussions about things like the Confederate statue — something she admits she’s conflicted about.

“I admire the attempts by the county commissioners to try to work this out, to create an atmosphere of reconciliation,” Perry said

And Bob Pearson, she says, is “a master at reconciliation.” Perry said Pearson’s efforts to memorialize the lynching victims has coincided with discussions she’s been involved in with her own Quaker congregation in Alamance County. As a member of the NAACP, she admires the effort and recognizes its value. But for various reasons, she says she’s reluctant to leverage her political position (she’s not seeking re-election as mayor this year) in an advocacy role. In addition, she thinks it’s not her place to decide, anyway.

“It seems presumptuous for me, or anyone who’s in a political position, to try to implement recognition on the part of the white community or the black community,” Perry said in a recent conversation in her office inside Pittsboro’s town hall. “In the black community, some of the people I’ve talked to so far say, ‘We don’t need to be reminded of the lynchings — that’s not something we perceive is going to pull us together.’

“It was a terrible time,” she says, “and let’s hope it’s never re-created. But I don’t know how you take those two dichotomies and bring them together.”

Perry reflects on a recent conversation she had with a Pittsboro resident about the Confederate statue at the historic courthouse in the center of town.

“It doesn’t make any difference what you put up at the courthouse,” she remembers being told. “What makes a difference is what you feel in your heart — whether it’s regret that it happened, or empathy with black people in the community who feel one way or another.”

For Perry, that’s an important sentiment. But still…

“As a white person,” she says, “I’m not sure I need to make a decision about what’s going to make the black community feel better.”

One member of that black community, Pittsboro’s Mike Wiley, has been writing and performing plays that tell of the struggles of African-Americans for about 15 years. In that time, he says, telling about the struggle has become more relevant today than ever.

“Sadly and tragically, it has not become less important to share those stories,” he said. “We’ve got this ‘silly season’ in America now — and I call it that because there are quite a few fools who still want to deny the true lineage of racism and lynching and marginalization, not just in the South but across the country.”

It’s important to keep the stories, “these true histories,” he says, alive in the minds of young and old alike “so that we don’t repeat history.”

History doesn’t often repeat itself, he says, but sometimes “it sure does rhyme, and it’s rhyming with a strong cadence and beat here lately.”

5. A bloody past

Like others, Wiley says America hasn’t reconciled with its bloody past. Part of the goal of his performances — one of which, “Dar He,” tells the story of the murder of Emmett Till, probably the most highly-publicized lynching in American history — is to help people understand history by walking in it in a dramatic live performance.

“Even today, there are more people willing to say that they had nothing to do with it, or that their ancestors had nothing to do with it, than there are those who want to really understand that history and how it is affecting the lives we live today,” Wiley says, “…how white people have had an advantage over people of color for centuries in this country. To not atone for that, and to not see that truth — that is what is keeping our country, our population, from being able to truly come together, to reconcile, to have these kinds of conversations that need to be had.”

History, he says, is “the water we swim in, the air we breathe. It is who we are. We cannot separate ourselves from our past any more than we can lop off a limb and not miss it, and therefore the importance of understanding these stories is that growth comes out of truth.”

The history includes the mentality that pre-dated and allowed lynching, and exists today.

“The mentality is very straightforward,” says Crawford. “It doesn’t require a Ph.D to understand it’s white supremacy.”

But Crawford is among those who wonder how a memorial will help move the discussion forward, given that it might be construed by some to be a representation of victimhood.

“You know, we don’t need to go dig through our ancestors’ bones to find the place where reconciliation needs to happen,” he says. “It’s here, it’s now. I don’t want to fault the effort, and if a sufficient number of people want to have a memorial to it…

“I just want to say that I’m not sure that it achieves the goal, and I fear that it’s merely a reverse image of the power and the nastiness of white supremacy. People should know about it, be aware of it. We should talk about it and it should be understood. But a memorial, I’m not convinced yet...but I am open to the argument because people may have compelling reasons.”

Existing white supremacy is one of the most compelling, Crawford says.

“I think that form of white supremacy here and now is an issue that doesn’t require reading a whole lot of history to understand,” he said. “You are defining America with meets and bounds where the people you like are in and the people you don’t like are out. The rest of us aren’t OK with that, and we’re going to point it out each and every time, and it might make you feel uncomfortable; it might make you feel like your heritage is being attacked. Then we ask that you put that piece of heritage either in proper perspective or just put it aside.”

Mills, the Politics North Carolina founder, warns in his aforementioned essay that Americans can’t gloss over the horrors of slavery or of Jim Crow as we teach about our shared history.

“We also can’t bend to the backlash from reactionaries who use victimization as an excuse for violence,” he writes. “We need to address the structural barriers to opportunity that are far less visible than the laws that enforced segregation. Fixing the damage our government caused to an entire segment of our society will take more than just 50 years. We can start by being more honest with ourselves and with future generations.”

And that will take time, which Pearson admits.

“We’re not trying to rush it,” Pearson says of the effort, which he and others are nurturing along quietly. “We’re having a conversation in the community that may take some time to bring to a conclusion. We’re getting started and we’re encouraged about what we see.”

Perhaps it’s too early in the work to assess opposition — particularly in light of the rancorous debate around the fate of the “Our Confederate Hero” statue — but Pearson stresses: when it comes to memorializing the victims and building a framework around the discussion of the legacy of lynching, and around the notion of reconciliation, it’s important to remember that this specific initiative is FOR something, not against.

“Reconciliation doesn’t require that everyone completely agree, but it lets everyone understand what happened and think about its effects down through the years,” he says. “In my experience, it always leads to progress based on a shared knowledge.”

He reminds the community that the Equal Justice Community Remembrance project is non-partisan, non-confrontational and non-violent.

“White and black communities in more than 300 counties in this country already are working together on these Equal Justice projects,” Pearson says. “We are having a community-wide discussion with one purpose in mind: to recognize and respect all the history of Chatham County and use it as a foundation for building a better community.”

It is natural and expected that a history of actual events that occurred here should be understood, respected and recognized, he says, because “it will change the way we look at history, understand history, and understand the people who went through that history.

“We will be reaching out as we have already to talk with everyone interested in knowing about the history and discussing it,” he said. “Memorializing that history could take many forms: discussions, artistic exhibits, speaking events, education, essay competitions, presentations to interested groups, and should include a physical representation for all to see and learn from.”

It’s in the looking, Crawford says, that we’ll find a path.

“It’s a reset button on the question,” he says, “but I know, as well as you, the argument that there needs to be a new cultural understanding will be denounced as a new attempt at brainwashing. But if we get everybody to focus on the facts, the facts, the facts, the facts, and base your interpretive claims upon the facts, then we’re going somewhere.”