Editor’s note: In this first of a series of reports, the News + Record is examining school equity in Chatham and across the state — providing a broad view of the major metrics of equity, how Chatham County Schools is addressing existing disparities and what CCS and other local organizations are doing to combat those gaps. Future installments in the series will provide a deeper dive into various areas of school equity.

Throughout remote learning over the last year, many people argued that schools should reopen based largely on students’ deteriorating mental health and worsening academics.

But as schools begin reopening, education experts warn that long-standing educational disparities have only deepened during remote learning and won’t be fixed simply by returning to school — at least not for all students.

Before the pandemic, multiple metrics of student success revealed sharp disparities in race and income. Achievement gaps — which occur when one group of students outperforms another group — between white students and students of color remain mostly unchanged in recent decades. Other metrics such as discipline, graduation and summer learning loss rates negatively skew toward low-income students and students of color.

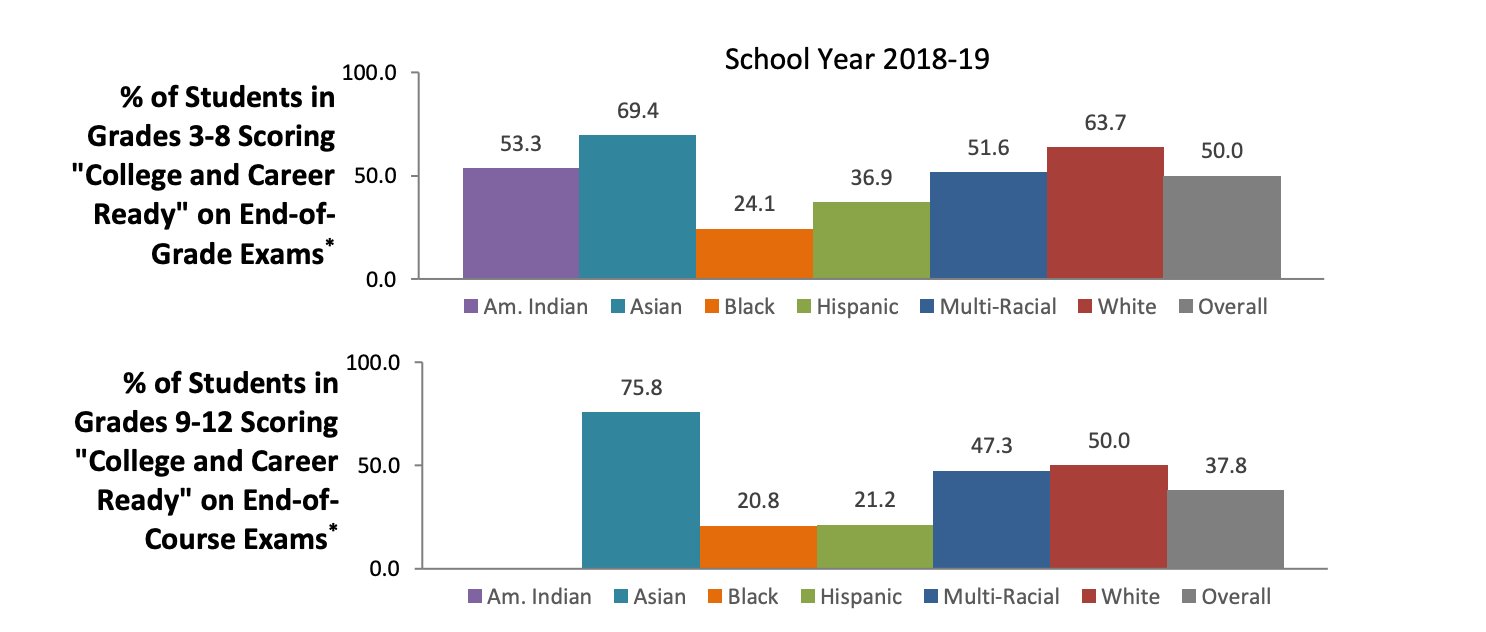

Many of those problems exist in Chatham, too. According to the Southern Coalition for Social Justice’s 2019 Racial Equity Report Card (RERCs), white students at CCS in 3rd-8th grades were 2.6 times more likely to score “Career and College Ready” on final exams than Black students — a discrepancy that occured in neighboring school districts at a similar rate.

According to the same report, Black students were also 4 times more likely than white students to receive a short-term suspension. CCS’s suspension rate fell between neighboring districts’ rates. Black students at Chapel-Hill Carrboro Schools were 10.4 times as likely to receive short-term suspensions while in Orange County Schools, the rate was 2.8 times as likely.

Amanda Hartness, CCS assistant superintendent of academic services and instructional support, said the district began formally addressing equity issues through the creation of its Equity and Excellence for Everyone (E3) team more than five years ago. The team, which has representatives from each of the district’s 19 schools, works to support students by eliminating barriers for student groups as well as by using and providing culturally relevant resources across the system. Hartness said over the last few years the district revised various policies, such as dress code and discipline, made language on district forms more gender inclusive and added more diverse texts and curriculum to classrooms.

“Another area that I would say that we’re proud of is achievement — we still have a lot of work to do with closing achievement gaps, but we’ve been able to move several of our low-performing schools out of that status,” Hartness said. “We’ve also closed achievement gaps in a couple of different areas by 15 to 20 percentage points, depending on the area. But we have a lot of work to do still, and so that continues to be a challenge that we’ll have.”

Equity in education ensures that every student has an equal chance for success, something advocates say requires proactive policies and systemic change to address underlying inequities and barriers. Chatham Education Foundation Executive Director Jaime Detzi emphasized that education equity efforts should begin before students start school.

“The most important thing is that all of our students have access to the same opportunity, and that starts from the day they’re born to the day they leave our school system,” Detzi said. “Having access to similar opportunities is probably one of the most important things, knowing that every student needs different opportunities to succeed.”

Hartness said that along with race and income, the district’s equity efforts also focus on sexual orientation, religion, gender and any other protected class.

“We’re trying to look at everything we do as a district and trying to make sure that we’re meeting the needs of all students,” she said. “And that’s the crux of it.”

North Carolina’s Constitution grants everyone the “right to the privilege of education,” which is the state’s duty to “guard and maintain.” Article IX also mandates that the state’s free public schools must provide “equal opportunities” for all students.

In 1997, North Carolina’s Supreme Court clarified those rights even further in a landmark court case, Leandro v. State. The court ruled that North Carolina’s Constitution guarantees “every child of this state an opportunity to receive a sound basic education” in the public school system.

“An education that does not serve the purpose of preparing students to participate and compete in the society in which they live and work is devoid of substance and is constitutionally inadequate,” the ruling read.

Over two decades later, North Carolina has not yet been able to comply with that decision, according to an independent WestEd report commissioned by Judge W. David Lee in 2018 to provide the state policy recommendations for compliance.

“Although North Carolina has had a deep and long-standing commitment to public education to support both the social and the economic welfare of its citizens, the state has struggled with fulfilling this commitment for all of its children,” that 2018 report said. “... Children of North Carolina deserve better.”

In addition to achievement gaps — found in end-of-year testing scores, literacy skills and graduation and college acceptance rates — many schools also have disparities in discipline rates and summer learning loss. Additionally, a lack of schoolwide accessibility for English Language learners and their families can create challenges for these students that lead to learning gaps.

These problems are not specific to one place, and while schools have a responsibility to correct these inequities, many start before and outside of the classroom.

“This is not Chatham County-based, but statistics show that two-thirds of low-income students don’t have books in their homes, few if any,” Detzi said regarding periods of learning loss. “... even just the most basic of leveling that playing field is making sure that those kids have books that they can read. And they can go to a library, but can they get to the library? I mean, maybe not.”

Another gap seen in many North Carolina school districts is the diversity of school staff, along with the retention of diverse faculty members. At CCS, 83% of its teachers are white, according to the 2019 RERC; 51% of its students are white. Little representation among faculty can lead to minority students feeling less understood or supported.

Before the pandemic, Hartness said CCS hosted focus groups to get student insight on equity concerns. She said one reflection came up often: the best teachers are the ones who know how to facilitate classroom discussion. Students cited feeling less secure or comfortable with teachers who didn’t know how to address controversial or problematic topics.

“That was interesting to me that our kids were able to pick up on the fact that our teachers need more training — on all the things they could have said that they wanted as kids for us to do as a district, it was to train our teachers,” Hartness said. “I thought that was pretty insightful. So I think that’s probably one of the biggest challenges that we have moving forward is how to help train our teaching staff on knowing how to do this work.”

CCS’s equity team recently began its district equity training efforts with a group called The Equity Collaborative, which will take place over the next two years. The district is also working with that group on an equity assessment, which will involve talking to all levels of school community members and looking at schoolwide data.

The team will share more of its efforts and plan moving forward at the Chatham County Board of Education’s April 19 meeting, Hartness said.

Many local organizations have also mobilized to work toward filling in these gaps. According to Detzi, Chatham Education Foundation seeks to close gaps in literacy, which she calls “the bridge to success.” Recently, CEF has begun to focus on early learning, too, she added since that’s “the key driver to making that gap close faster.”

CEF has also funded several district equity initiatives, including the Chatham County Schools’ Kindergarten Readiness Camp and the Math 180 program. The Kindergarten Readiness Camp helped prepare children with little to no preschool experience for kindergarten, while the Math 180 program that tutored rising ninth graders who didn’t meet math proficiency standards.

Communities In Schools of Chatham County works within schools to provide at-risk students with a support network; they also seek to empower students to achieve academically and stay in school.

Other programs specifically support high school and college students. Chatham Promise, an agreement between Chatham County and Central Carolina Community College, funds two years’ of tuition at CCCC for qualifying residents who graduated from a public high school.

Founded in 2017, Orgullo Latinx Pride, or OLP, seeks to empower high-school aged Latinx youth and provide them the necessary tools to pursue higher education. It’s also the Hispanic Liaison’s youth leadership program.

The free, yearlong program typically takes on 25 to 30 teenagers each school year — and according to youth coordinator, Selina Lopez, 100% of OLP alumni have gone on to attend some form of higher education after graduating high school.

“A lot of (Latinx youth) do get left behind because either they’re not qualified to be in programs like AVID,” Lopez told the News + Record last fall, adding, “Our goal is to really have them pursue higher education, but it’s not an academic program. ... A lot of times it’s just no one has ever spoken to them about college or university and this idea of it being possible.”

As CCS works on implementing its upcoming equity-related projects, the district will also be writing a new equity strategic plan. This plan — and its equity work overall — focuses on three main buckets: relationships, policies and practice and curriculum and instruction.

The impact of the pandemic on such efforts cannot be understated. While many of the pandemic’s impacts on learning are still being discovered, emerging data suggests that students are failing classes and exams at much higher rates — and that the disparities that existed between student groups before the pandemic are widening.

As students and teachers return to in-person learning then, experts say a focus on equity will be crucial in ensuring the return to school doesn’t just serve as a return to previous rates of disparity.

Hartness said the district is ready to tackle these issues — to continue making headway in the district’s motto: collectively creating success.

“It’s exciting to me that we’re really kind of rolling up our sleeves and starting to dig deep in the work,” she said, “because it matters for our students.”

Reporter Hannah McClellan can be reached at hannah@chathamnr.com or on Twitter at @HannerMcClellan. Reporter Victoria Johnson can be reached at victoria@chathamnr.com.