Editor’s Note: This is the first of a two-part series about child abuse and neglect in Chatham County. The series concludes next week.

In his 2014 book “The Body Keeps the Score,” Boston University psychiatry professor Dr. Bessel van der Kolk explores the deep and lasting impacts of trauma.

It’s not pretty.

“One does not have to be a combat soldier, or visit a refugee camp in Syria or the Congo to encounter trauma,” he writes on the book’s opening page. “Trauma happens to us, our friends, our families, and our neighbors.”

Dr. van der Kolk cites research from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention about those growing up: one in five Americans are sexually molested as child, one in four received beatings by parents that left a mark, one in four grew up with alcoholic relatives and one in eight witnessed their mother being beaten or hit.

Those things leave a proverbial scar, he says.

“While we all want to move beyond trauma, the part of our brain that is devoted to ensuring our survival (deep below our rational brain) is not very good at denial,” Dr. van der Kolk writes. “Long after a traumatic experience is over, it may be reactivated at the slightest hint of danger and mobilized disturbed brain circuits and secrete massive amounts of stress hormones.”

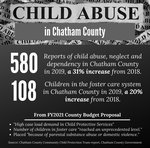

Chatham County’s children experience this — and the numbers that are more at-risk to do so are growing. In the calendar year of 2019, there were 580 reports of child abuse, neglect and dependency to the Chatham County Department of Social Services — a 31 percent increase over 2018. On average, there were 108 children in foster care, a 20 percent increase over the previous year. The proposed county government budget for the 2020-2021 fiscal year asks for three new social worker positions within DSS “to address the high case load demand in Child Protective Services” and says the number of children in foster care “reached an unprecedented level,” with many children placed “because of parental substance abuse or domestic violence.”

Those involved in putting the report together that shows this data — the county’s Community Child Protection Team (CCPT) — say they don’t know the cause.

“We have tried every which way to figure this out, to understand why is this happening now, and we don’t know why,” said Jennie Kristiansen, Chatham County’s director of social services. “We know that it’s increasing and we know, for example, that we’re seeing more frequent substance use, families with serious substance use disorders. But we don’t know why.”

What is certain, however, are the long-term effects on children who are abused or neglected, and how they affect an entire community.

What child abuse looks like

Hilary Cissokho, a social worker with Chatham DSS, said most cases the department sees usually have at least one of three different factors: parental substance abuse, untreated parental mental health and domestic violence in the home.

Of the nearly 350 reports to Chatham Child Protective Services that were investigated last year, nearly a quarter involved allegations of substance use, the CCPT report stated. Kristiansen said that about 70 percent of the children in foster care were pulled from homes with substance use issues.

The report also pulled out six individual cases involving 14 children, “specifically selected because of the difficulties faced in improving outcomes for the families.” In each of the six families, one or both parents had substance use disorders that required inpatient or outpatient treatment. Four families had a history of domestic violence that involved law enforcement. Nine of the 14 children had “identified mental health diagnoses or Intellectual/Developmental Disabilities.” Sexual abuse allegations were present in three cases.

Most of what Chatham DSS sees, Cissokho said, deals with neglect.

“If a parent is actively abusing substances, what ends up getting reported is inappropriate supervision,” she said. “A parent leaving their children home alone because maybe they’ve gone out to use or being so high or altered that maybe they are asleep that someone can’t wake them — you’re seeing the other impacts on the child.”

The department also gets reports “fairly frequently” of babies born with prenatal exposure to substance use.

“If a child is born and starts having withdrawal symptoms and respiratory distress, they are going to be screening for what’s going on,” she said.

A positive test leads to a DSS report. A 2018 report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services said 27,709 children across the country were referred to CPS that year in those kinds of situations.

Victims of more severe cases, those involving felony charges, are referred to Anne Chapman, the program director for Chatham County Child Victim Services. Chapman said the cases she sees often involve indecent liberties, rape of a child under 15 and sexual battery — all sexual abuse crimes. She said she doesn’t have specific statistics of how many of each happened, but that the numbers are “not that different” than national statistics.

“All the kids on my caseload have been the victim of a felony crime, or there’s been an accusation of a felony crime,” Chapman said. “If they stay on, that means it was substantiated, and usually what we know from all of the data and all of the social science studies is that kids don’t lie about this stuff.”

A separation

A DSS case that leads to children being taken from their parents is a tricky one, for everyone. And there’s no right answer.

Given the increasing number of Chatham children being placed into foster care, it’s important to define the process of pulling a child out of their parent(s)’s home and into foster care.

An individual makes an anonymous report to DSS, and a DSS employee conducts a standardized assessment of the situation. If the cases warrants more investigation, it becomes “screened-in.” An investigator will look into the situation and provide guidance to the family — “many cases” end there, Cissokho said. But if the issues are more significant, the cases is passed to someone else for either in-home services or removing the child, something that happens if the child is “in imminent risk,” Cissokho said.

Even though it might be best for the child to be out of their home and with a foster family, it’s still a rough experience.

“Being removed from the home is very traumatic,” Cissokho said. “No matter how bad the things at home are, the majority of kids really want to go home. It’s really hard. We’re asking a lot of kids to be adaptable.”

Susanne Saunders, a therapist who operates a private practice in Pittsboro, has worked with children placed in foster care or adopted throughout her career and said this kind of separation is trauma “with a big T.”

“They’re leaving everything they know,” she said, “because they don’t know that what they’re in is necessarily a bad thing.”

DSS will usually look to other family for placement first, but if that’s not possible, foster care with new people, strangers is the next choice.

“If they can’t do that, then they’re going into homes where they don’t know anybody,” Saunders said. “It’s like jumping off a cliff. The big question is, who can you trust in all this? They’ve talked to law enforcement, they’ve talked to DSS, they’ve talked to, perhaps a forensic evaluator, then they get assigned to a therapist, there’s a case manager and then there’s a GAL [Guardian ad Litem]. So there suddenly are many new adults in this person’s life. If they were in a home where there was abuse and neglect, trust is always going to be an issue anyway.”

The impact of trauma

Science’s understanding of trauma is relatively new, but what studies and research have revealed is that devastating events in childhood can have lasting effects. It’s not just an immediate impact — in some cases, it can be lifelong.

“When something reminds traumatized people of the past, their right brain reacts as if the traumatic event were happening in the present,” Dr. van der Kolk writes in “The Brain Keeps the Score.” “But because their left brain is not working very well, they may not be aware that they are re-experiencing and reenacting the past — they are just furious, terrified, enraged, ashamed or frozen.”

Additionally, he writes, stress hormones of those who experienced trauma “take much longer to return to the baseline and spike quickly and disproportionately in response to mildly stressful stimuli.” Essentially, if you have childhood trauma and something happens as an adult that sparks a memory of that, you are more likely to respond much more emotionally to that instance, and you’ll “return to normal” much slower than others.

And this trauma is often hidden from the world, or misunderstood by those who haven’t gone through it as well.

“Traumatized people look at the world in a fundamentally different way from other people,” Dr. van der Kolk writes. “For most of us a man coming down the street is just someone taking a walk. A rape victim, however, may see a person who is about to molest her and go into a panic. A stern schoolteacher may be an intimidating presence for an average kid, but for a child whose stepfather beats him up, she may represent a torturer and precipitate a rage attack of a terrified cowering in the corner.”

Saunders specifically spoke to children who have experienced sexual abuse and emotional abuse. Sexual abuse, she said, like the ones referred to Chapman’s department, can take “a long time to recover from” and can be relived at different stages of life.

“Somebody that comes in, maybe as a teenager, young teenager for sexual abuse — I might see that person five years later, (someone) who’s resolved some things and have moved on through their life,” Saunders said. “But something new triggered it and we have to revisit it.”

Emotional abuse, however, can sometimes be much worse.

“It’s the emotional abuse that stays with us longest that stays with us longest through the lifetime, which is quite remarkable,” she said. “So in other words, you may have recovered from childhood sexual abuse, but there’s always going to be an emotional impact from that, and that is the hardest piece.”

Working with these cases

Finding a way to cope with working in this field is crucial, Cissokho said.

“It is difficult to see kids who are hurt, and those who are let down,” she said. “DSS cases are rarely straight-forward. Working with a child on getting back home is often a bumpy road, and that’s really hard to see.”

Cissokho’s undergraduate degree is in music therapy, and she has a master’s in social work. So she’s educated for this. She had what she called a “healthy childhood” in Chatham County, and seeing others who didn’t motivated her to step in and try to help.

“I was really unaware of the people who were really struggling, right here in my own community,” she said. “I think once you are aware, it’s hard to look away from that. The more I know about the needs in our community, the more I feel called to do my small part to meet those needs.”

Chapman rides her horse to get away from the stress of her job. She also invests in prevention and outreach work, regularly speaking to kindergarten, 2nd grade and 4th grade students about appropriate touching and consent.

“I get to go in and work with kids who are just normal, happy kids living their lives,” Chapman said. “And yes, I hate to have to come in and tell them things. But I do it in a way that’s really positive and I strive really hard to preserve their innocence and teach it in a way that’s empowering, and light and fun. We’re not talking about it in the context of sex or anything like that. It’s just in the context of, ‘Hey, nobody should touch you in the private area of your body. And if they do, you should tell somebody.’”

Saunders worked at the Family Violence and Rape Crisis Center, Chatham’s former domestic violence agency, for 10 years, often working with kids who had been exposed to violence or abuse or were victims themselves. She said she wants to give kids an opportunity to express themselves in hopes of identifying their feelings.

“I don’t try to impose an adult world on a kid,” she said. “I’m really trying to find out what the child’s going through in a way that doesn’t make it so that, ‘Whoa, here’s one more person I have to have the answers to.’ Trying to keep it open-ended and giving them space over time that they can get more comfortable. Many kids haven’t had a chance to really sit and say, ‘Well, how do I feel about that?’”

Reporter Zachary Horner can be reached at zhorner@chathamnr.com or on Twitter at @ZachHornerCNR.