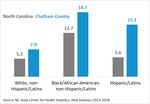

In Chatham County, infant mortality rates are higher among both Black and Hispanic residents than white residents — 18.7 per 1,000 live births and 15.1, compared with 7.9. A larger percentage of Hispanic/Latinx high school students in Chatham have felt sad or hopeless nearly every day for two weeks — a primary symptom of depression — compared with white students. And a lower percentage of non-white and Hispanic/Latinx Medicare fee-for-service enrollees in the county had an annual flu vaccination compared to white Medicare enrollees.

These are just a few of the findings from the Chatham County Public Health Department’s recently released report, “Spotlight on Health Disparities in Chatham County.” The report is part of the department’s work to pursue health equity in the community.

“The CCPHD’s vision is: ‘A fair and inclusive Chatham County where all residents achieve their best physical, mental and emotional health and feel a sense of belonging,’” the report, available on the county’s website, said. “To achieve this aim, we seek to better understand the health disparities that exist in our community and the inequities in which they are rooted.”

The report defines health disparities as preventable differences in health outcomes between groups in our society, which “occur across many dimensions, including race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, age, location, gender, disability status, and sexual orientation.”

Health disparities, the report said, are the consequence of “structural inequities that push communities into the margins and create the external factors that redirect, reduce, and remove opportunities to achieve optimal health.

“They are not the result of holding a certain identity,” according to the report. “Identifying as Black/African American, Hispanic/Latinx, LGBTQIA, a person with disabilities, a woman is not the risk factor. The risk factor is how systems and biases are constructed against diverse identities that lead to negative health outcomes. Our role as a local public health department is to understand these disparities and their causes and use that understanding to devise multi-level interventions to improve the health and well-being of all Chatham residents.”

The department said its hopes to develop a more comprehensive data-driven understanding of health in future years, emphasizing that their findings are not a complete representation of inequities in Chatham, but rather a snapshot. The work in the report builds off of the department’s previous reports on health disparities in 2010, 2014 and 2018.

The report not only examines disparities in various health outcomes, including rates related to COVID-19, maternity wellness and mental health; it also looks at social determinants of health, which include safe and affordable housing, access to education and environments free of life-threatening toxins.

“When we look at overall numbers, Chatham does really well on a lot of metrics, especially compared to around the state,” said Maia Fulton-Black, a population health data scientist who worked on the report. “But I think when we see when we break that down that’s where we start to see differences in different groups around the county.”

“As a health department, it is our mission to promote health and help our entire community achieve their optimal health,” added Casey Hilliard, Interim Director, Health Promotion and Policy Division. “If we’re just looking at overall numbers, then we aren’t actually doing our job. And so being able to break this data down and track it and understand it on that more detailed level, it allows us to then think about solutions and opportunities for us to improve the health for everyone in our community.”

Chatham County has experienced double-digit growth since 2010, the report said, but two-thirds of the nearly 75,000 people living in Chatham live in rural areas. The county is 82.2% white, 12.4% Black/African American, with 5.4% identified as “other,” including Asian and American Indian/Alaska Native. A little more than 12% of residents identify as Hispanic/Latinx.

Chatham’s median income is $66,857, with an unemployment rate of 3.9% and poverty rate of 13.3% — meaning it performs well compared to other counties and the state as a whole, the state said. However, as mentioned by Fulton-Black, there are disparities within these numbers. According to the report, Black/African-American households are two times more likely and Hispanic/Latinx households are three times more likely to be living in poverty when compared to White non-Hispanic/Latinx households, and life expectancy for members of the Black/African-Americans population is nearly five years shorter than White residents.

“Disparities can also be seen visually across Chatham when looking at a map. For instance, poverty rates in the northeast corner of the county are three to four times lower, and the median income is nearly two times higher, than in the southwest corner,” the report said. “Siler City, located in the western part of the county, has a median income under $35,000 and an unemployment rate of 9.8%. Taken together, these point to inequities across our community that coincide with well-documented outcomes across the state and country.”

Michelle Wright, equity and community engagement lead in Chatham, said it’s important to realize that seeing significant changes in these sorts of trends is “very long-term work.” Life expectancy, for example, is not the type of indicator that would shift within a year or two, she said.

That being said, the department is working hard to ensure that over time, change in trends is possible, Communications Specialist Zachary Horner said.

“We are committed as a department to doing everything we can, and to using the resources we have to move forward and to hopefully one day reach health equity,” he said. “Until we’re there we’ll keep working as hard as we can. And sometimes, we need to be reminded of the reality of ... these issues of these health disparities, and this report is a snapshot in time of where we are.”

On Aug. 24, the Chatham County Board of Health voted to declare racism as an ongoing public health crisis, pledging its commitment in working to mitigate associated health disparities. Since the board unanimously approved that statement, which was largely well received, some residents have pushed back, claiming the statement is pushing a political agenda or is not based in fact.

“What we are addressing is an objective reality,” Wright said regarding such claims, adding that the department can specifically point to where every piece of data in its report comes from. “We would encourage you to look at this and to acknowledge that the experiences, the life experience of someone who is in a marginalized population, is very different. When you have different levels of privilege, you experience different things.”

Fulton-Black added that behind the data are real people in Chatham — neighbors, families, friends. She said she hopes people come to the report with an open mind, recognizing that these numbers represent people who are having very real experiences.

“It’s OK to not know about it,” Wright said. “But it’s best to be open-minded to learn about it, and acknowledge that if you haven’t lived a certain experience, that there is much that you can learn.”

Reporter Hannah McClellan can be reached at hannah@chathamnr.com.