During Black History Month, the News + Record will feature issues related to the African American experience in our Chatham Chats. This week, we speak with Chatham County resident David Warren, who serves as co-chairperson for the N.C. Freedom Park project.

North Carolina is one of only a few states which has yet to honor the African American struggle for freedom from slavery, Jim Crow segregation and racial discrimination with a monument. N.C. Freedom Park, which will be constructed on a one-acre site between the state legislature and the Governor’s Mansion in Raleigh, and will offer a place for school children, visitors, residents, citizens and policymakers to learn about the contributions of African Americans toward a better society.

A native of Chicago, Warren is a graduate of Miami University and Duke University. A former U.S. Naval supply officer, he had professorships at the UNC School of Government (1964-1974) and Duke (1975-2000), and was named professor emeritus for Duke’s Family Medicine and Community Health program in 2001.

Warren served as director of the Governor’s Institute on Alcohol and Substance Abuse from 1990-1997 and was a Fulbright Lecturer in China in 1998, 1999 and 2001.

What is the North Carolina Freedom Park and how did it come about?

Recognizing the lack of public monuments for African Americans, the Paul Green Foundation conducted in 2001 a series of town hall meetings across the state to explore ideas to honor the African American struggle for freedom. The result was support for a public park to be built in the state’s capital city of Raleigh that would be both commemorative and educational. A biracial statewide group was incorporated in 2004 with support from the Paul Green Foundation and the State Arts Council to pursue planning and funding for this monumental project.

Initial fundraising efforts coincided with a recession. Did you have other difficulties getting the project off the ground?

Over several years of both encouragement and disappointment, an initial design failed to draw financial support and determining a site for the park was delayed. Finally, in 2012 the governor and Council of State granted a lease for a one-acre space for the park across from the State Legislative Building and near downtown Raleigh’s museums — a prime location. Then the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation provided a series of grants to restructure the project and give it new energy.

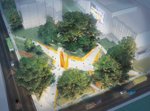

The next step was a smaller and more active board of directors and, fortuitously, a new design for the park created by the renowned architect Phil Freelon.

He had just completed his work as lead architect on the new National Museum of African American History and Culture on the Mall. Now we had an inspiring design that we felt would gain financial support. In addition, an influential business leader joined our cause and was able to find major donors to make substantial pledges for the project.

What is the park’s status now?

The fundraising for the park was boosted by a $500,000 challenge grant from the State Employees Credit Union and a similar pledge from the Local Government Federal Credit Union. That attracted enthusiastic support from nearly all the banks in the state plus large corporations such as Duke Energy. Crucial were grants from several of the large foundations in the state, including the A. J. Fletcher Foundation and the Kenan Charitable Trust.

Notably, two individuals generously wrote checks for $100,000 each. Then some supportive leaders in the General Assembly in June 2020 were instrumental in adopting a $1.5 million grant to enable the project to meet the threshold for starting construction. Thus, a ceremonial groundbreaking event was held last October and Gov. Cooper gave the park a big sendoff. Actual construction of the $4.5 million project will begin sometime this spring and be completed in a year.

The goal of the park is to honor the African American experience and contributions toward the promotion of freedom for all peoples. How will the park be used?

Upon completion of the park, the state lease agreement requires that it be transferred to the state for maintenance and programming. We are in continuous conversation with the N.C. Dept. of Natural and Cultural Resources about the development of the park and how it can be used to have an immediate and dramatic impact as a place for education and racial reconciliation.

The director of the department’s African American Heritage Commission is an ex-officio member of our board of directors and supports our proposal for a Friends of the Park organization to raise supplemental funds and provide expertise for programming in the Park.

We anticipate thousands of school kids coming in buses from all parts of the state to Raleigh as part of their N.C. history curriculum to visit the park and learn more about the African American story. Within the walkways in the park will be numerous quotations from North Carolina African Americans about various perspectives of freedom. For example, Ella Baker, the civil rights leader, says, “Remember, we are not fighting for the freedom of the Negro alone, but for the freedom of the human spirit, a larger freedom that encompasses all mankind.”

Besides the quotations on the park’s walkways, what other features of the park will attract visitors?

The central architectural feature of the park will be the gleaming 40-feet tall Beacon of Freedom. It will be a golden torch-like tower that will be symbolic of another quote, “My father passed the torch to me, which I have never let go out,” by Lyda Moore Merrick, an editor and advocate for the blind who was also the daughter of the founder of M&F Bank. (By the way, the quotations will all have electronic chips that will tell a backstory on smartphones.)

At the base of the beacon will be a gathering area for lectures, musical and dramatic performances, and, hopefully, conversations among visitors about the importance of the concepts of freedom, namely, justice, equity and opportunity. To facilitate the educational impact of the park, docents will be available to interpret and elaborate on the message of the park.

How did you get involved in the project, and are you the chief spokesman?

I am certainly an advocate but others on our talented board can better speak for the park. On our website (www.ncfmp.org) are videos of Freelon (our acclaimed architect, now departed), Reg Hildebrand (former UNC African American history professor) and others who tell the story. My job as co-chair, along with Goldie Frinks Wells (who currently serves on the Greensboro City Council) is to coordinate the enthusiasm that this project has generated. That means accompanying board members on donor visits, keeping legislative leaders well informed, doing some of the legal work behind the scenes and following up with news media on inquiries about the progress of the park.

In the early days, my wife Marsha — as director of the Paul Green Foundation — was pushing the project and needed a lawyer to incorporate the effort. She volunteered me and I found myself caught up in what I now know will become an iconic landmark in these times of heightened sensitivity to African American justice.

How can we find out more?